AI discussion panel „What does AI do to art?“

This panel took place at at DAM Projects on June 29th, 2023 with Tilman Baumgärtel, Pamela Scorzin and Harm van den Dorpel and was moderated by Wolf Lieser.

WL: Welcome. The occasion for this panel or roundtable discussion was actually that in the years in which I have been following this development with artificial intelligence here in the gallery, I found repeatedly that on the one hand, the topic was communicated very unprofessionally or incompetently and on the other hand, was also partly mystified in the art scene.

I have tried to find a circle of participants in the conversation who are very well versed in this area and who can accordingly and competently talk about it. Including an artist who has been working with it for a long time. So I’m looking forward to tonight.

I will briefly introduce the participants:

On my left, Professor Doctor Pamela Scorzin. Professor of Art Science and Visual Culture at the Department of Design at Dortmund University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Pro Dean and Art Critic. Last year, if you know the magazine Kunstforum, she published a volume on the subject „Can AI make Art?“. So it’s just our topic.

Over here, Professor Doctor Tilman Baumgärtel. Author, media scientist, curator and journalist. Professor of Media Theory at the University of Applied Sciences in Mainz in the Department of Design, specialising in Media Design. One of the aspects for which he became very well known in the art scene were two books on net art already in 1999 and 2001.

And in the middle, Harm van den Dorpel. An artist with international reputation who has been shown in various exhibitions in museums and galleries, has also been very involved in the context of NFTs and has been dealing with the topic of AI for several years.

The first question would be to Pamela on my left, which is the view, or your view on AI. What would you describe as AI? How would you define it?

PS: That’s a very general, very broad question and you can answer it quickly. It depends on how you ask. If you ask computer scientists or someone who has really developed or programmed AI they would say: „That’s an algorithm and it’s about problem solving.“ So finding a solution and a creative solution to a problem. In the arts it’s of course different and I would say we talk about art tonight, or what AI is doing to art.

Do we need to differentiate in the round as well? Is it about creativity or is it about art? And then, what concept of art do we agree on? I would simply say that AI has become another tool that is used by artists to create art and perhaps here we can separate again.

There are many artists whose work is about AI, with AI and through AI. This is also relatively exciting and perhaps we shouldn’t take it the way the discussions are turning at the moment with Chat GPT or with Midjourney, DALL-E, etc. That’s only about generative images. So the spectrum is much wider and that’s what I tried to show in Kunstforum International in the volume that deliberately had the question in the title „Can AI make art?“. And tonight we are also asking: How does AI influence art? What does it do to art?

Perhaps as a first statement in the round, I would say that AI is a very intelligent new instrument. A new technology in the long history and development in which we’ve always used tools to make art. It has become more intelligent, it has a certain autonomy and with this autonomy it also becomes a co-producer or co-creative partner and co-player.

So I would say in short, AI enables a co-creativity in a wide network where we are human actors, artists. We humans who use the tool, the algorithm, but in a network. We produce something but it still needs the will. It needs the motivation of a human actor who wants to achieve something with it. So co-creativity, co-production, I would say, is the issue with AI. In a network.

WL: Yes, I can understand that. Tilman, how do you see it?

TB: Let me remind you that we had prepared small formulated statements. I don’t know wether this is the opportunity to get rid of them or if we’re going to wait, because I think you shortened up.

PS: I have shortened it a lot, I would say AI enables.

TB: Well I’ll try to summarise it briefly, it’s already been put on paper here and I would say there is no artificial intelligence at all.

The term was coined in 1956 by the American mathematician John McCarthy when he applied for funding for an academic conference and was looking for a cool buzz word to make this academic conference interesting. That was the famous conference at Dartmouth College in the USA, and that was a workshop that actually got all the money over the whole semester break in the summer, eight weeks long. And there were, for example, Marvin Minsky or Nathaniel Rochester or Claude Shannon. And it was through these people that the term came into circulation because Minsky, for example, played an important role in the AI for the following few decades. In quotation marks „AI research“, and used this term again and again where one could just as well have said Automata theory. That was a different title than the one McCarthy had in mind, or by the way, wanted to describe: Stochastic Process steering.

By the way, the term machine learning is equally a buzz word coined by IBM in 1959 for marketing purposes and yes, actually not really applicable. Back in the 1950s computers were not very intelligent in the sense of being independent or creative and are still not intelligent today. But what they can be or what they can produce, are new and ever more sophisticated methods. The computer, what we can do with it, is to use it as an instrument in creative work and entrust it with some tasks.

Since the 1950s artists have always been among the early adopters of this technology, if not actively involved in the development of new design methods with the computer. And I think that’s what we want to talk about today.

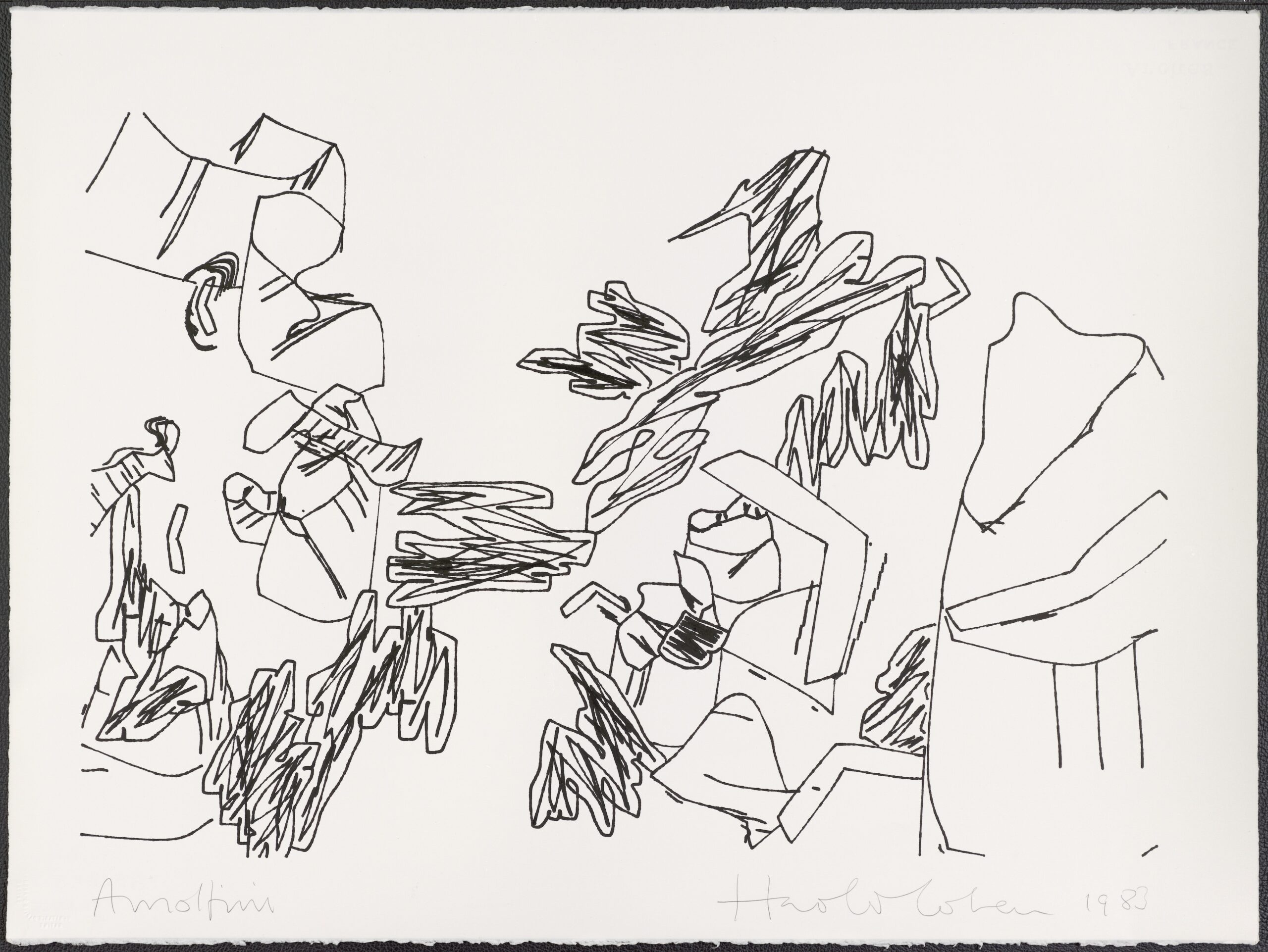

In the 70s, Harold Cohen, who since the late 1960s, after a successful career as a painter without a computer, turns to working with computers and generative work and also developed his own program, created the Aaron software, which really painted on its own. He said in an interview in 2009: „I don’t think so much about the autonomous program. That was also a certain learning curve that had been introduced. I think about the program as a collaborator.“ Something like what Pamela just said. That also applies to artists today and I am therefore curious to know what we will hear about the subject from the artist or maybe from the artists who are present here.

WL: Harm, before you present your position. There has been already a good introduction. As far as artists are concerned, there is an interesting development. Tilman already mentioned Harold Cohen had this idea as early as the 70s of really developing an artificial intelligence or a model. A computer program that can act so extensively on its own that it produces art for him.

When I met him, it was like this: he went down in the morning, the computer worked overnight, so he looked at the results, said: „We’ll take that, we won’t take that“ and those were the results from the previous night, and then he left again.

The big difference, we will certainly go into more detail on the subject, is that he had no input whatsoever. So he didn’t use any material from the internet, he didn’t have any data sets or images from the internet, which is something completely normal these days. This is also used in large quantities by artists, and it is a question of conceptually understanding where a structure or an interesting painting or drawing is created and how this is possible.

This system, which taught itself, developed itself, was absolutely revolutionary at the time. To my knowledge, the first who worked in this way as an early precursor was Cohen. Because the earlier pioneers worked with two-dimensional geometric shapes, that is, much simpler systems.

And now to you, Harm. How do you work with AI? How would you define AI? How important is it to you in your work?

HvdD: Yes, I like how you said that. There’s no AI at all, I happen to agree. It’s more of a complex, non-linear reproductive system. But it’s cool too. It is great too and you can get involved in a lot and I’ve been making generative art for a long time and arbitrariness is often used because random values are used randomly again and again.

I thought to myself how could I, because with humans in biology it isn’t like that, when you talk about evolution it’s not random. There is a direction that develops and it’s somehow better or more interesting, or adapted, adjusted. And then I thought: „What did I learn at university?“. I studied artificial intelligence, but didn’t use it directly for a few years and then found out if I could describe an image, i.e. a genetic structure with a chromosome, not with genes but with instructions on how to make one: make a circle, make a square, change the colour… And if I could then, for example, take two works that combine chromosomes with crossover and then recreate new children, I found that very exciting. And that actually worked relatively easily so I worked with genetic algorithms for a very long time.

And then the question is, is that an artificial intelligence?

No, there is nothing. It’s totally stupid, but it’s ok. It’s technology from the world of AI. I learned that at university and I kept looking for this moment, the moment when it would become intelligent, but it never came. It’s ok. It was very practical to say, I say this often in English, „tame the randomness“. There’s a direction there.

I recently did a generative project with about fifty parameters and I wanted to generate a thousand of them and I couldn’t do all by hand so that all thousand would be interesting, but also different. So I created twenty or thirty good works, saved them, and also saved around thirty bad works and told the neural network: „I think these are good, I don’t find these good and I find these average.“. After that, the neural network generated a thousand actually very acceptable works. Was that intelligent? Maybe I was a bit intelligent. I’m proud that it worked. But there’s no conscience in the neural network, there’s nothing there.

WL: Exactly, but you said you chose which ones you liked and which ones you didn’t like. That’s a very interesting aspect. As far as I know, an AI system cannot do that. There is, we can talk about it in a moment, there is this concept of GAN, where systems are in communication but… Which were the criteria for you?

HvdD: For example, I once did a project where I didn’t want to decide for myself what was good. So I thought about it, also in painting, what is a good picture? And I’ve always thought that a good picture has a certain amount of complexity. But it should also be transparent and simple at the same time. And I combined the two like this: I tried to save work from the image as large as possible and then divided it by the time it took to generate it and then I let the algorithm run for days and then something worked out.

But I’m also very, very, very happy to train my own networks. When there’s not so many layers, because Chat GPT has, I don’t know, millions. You can only train that with Big Data. But you can also easily create a network yourself and then train it. That’s really a lot of fun, to realise how fast they notice what you want.

TB: Yes, I was just about to ask, what’s totally interesting about Harold Cohen… As I said, he already had a career as a painter and he had developed his own style, his own handwriting. He was also relatively successful and he started to work with computers and somehow he managed to teach the computer his style. So these pictures that this software Aaron painted at some point looked like what he had painted before. And that was at a time when computers were still electronic brains, some of which took up entire rooms.

You have also made physical objects, I don’t think painted, but which kind of had a visual style. What are the common points? Have you managed to transfer your visual style?

HvdD: Yes, I find that very important, because as you say, this artist developed an AI himself. He programmed and worked on it for years and refined it and also trained there and again and gave it more input, also expanding the software in itself. For me as an artist it is an artistic process to develop software oneself. That’s where I make a lot of micro-decisions which I’m not always aware of and with that I somehow build a certain aesthetic.

What I actually find so uninteresting about things like DALL-E and Midjourney is that you give them a prompt, and it’s totally funny. We’ve got millions of pictures of pandas, we’ve got millions of pictures of skateboards, now we’ve got a panda on a skateboard, yay! It’s fine that people work with it, but they will only get a reproduction of something that already exists. There are no artistic interventions in the programming of these systems themselves. If someone took my concept and built the same thing again, it would look totally different because there are so many small decisions in the implementation.

PS: You could also say this with Midjourney, DALL-E and Stable Diffusion. It’s just a technological sequel that uses principles of sampling, mashups. We’ve seen that in the arts since the 90s, since hip-hop culture. The big question is: „Is something new emerging?“.

But of course we see in design or in the arts that exciting results have emerged, in mashup, in sampling or hip-hop itself as a culture. And to that extent it is also an emancipation. Today anyone can sample, even make a mashup, thanks to these intelligent tools. Of course we don’t know what’s behind, running in the background. That’s another discussion that might come up later, in the sense of a rip-off.

Today as a layman, anyone can use Midjourney if they have an account. That’s another question, the license, to have access to experiment, play, prompt… Sometimes there is a community that also cobbles together the prompts so you can also buy them. Because it’s quite an art to find the right one for this algorithm to get really interesting pictures. Exactly as you say, it doesn’t go any deeper into the matter or into the technology. But they’re an application and for me they are actually mashup mixers which are incredibly fun and enjoyable.

Another interesting question is, of course, wether the artist also needs coding knowledge. Because AI will of course be a more intelligent instrument and perhaps also a muse for the artist. But you have to have a certain level of expertise on the code level in order to be able to tune the instrument so finely for what you actually want to achieve later as an output.

Computer scientists always say: „Shitty input, shitty output.“. Whereas now with prompting we simply have our short texts and then we look forward to pictures which we then share on social media. By the way, that is new. The picture production is also published at the moment, instantly. And that actually serves to launch the images as a meme immediately on the internet.

That’s a completely different story than when it’s an artist’s job. I’m completely with you. Something is created in the network when I write a program that I work on again and again at the code level so that in the end it produces something that is meaningful, that has a meaning or also matches your goal. And in this case it’s an intelligent tool, I think.

WL: I just want to explain something briefly, for those of you who don’t know much about this area. „To prompt“ simply means that you enter a sentence, for example, any sentence of your creation which can produce an image.

PS: „Dear painter, paint something similar to me.“

WL: Something like that.

TB: Now I would like to say something briefly in this comparison with mashups and other collage techniques. It goes back much further, it really goes back to constructivism. And back then, you just worked with found material and there was a lot of material that actually had nothing to do with each other and was brought in contact and in dialogue.

That’s exactly what we’re seeing with these prompts now. People try the most blatant combinations somehow, because they see what the programme does. They enter „panda“ or something and for me that is warmed-up surrealism. That was the definition of André Breton: „Surrealism is the meeting of the umbrella and the sewing machine“, I think, „on the dissecting table.“.

And that is now, so to speak, somehow achievable for everyone without much effort. But I personally find that very uninteresting and there are a few artists who somehow draw attention to themselves with it for a short time. So I don’t think that has an enduring power.

And before we go to these coding issues, we should perhaps point out again that this is all based on a big act of copyright infringement. People went on the internet with big hoovers and appropriated everything that could be stolen from images. And yes, if you work with something like that, you only get very hackneyed images as a result.

I don’t know if you know what pulp is. When you make new paper out of waste paper. You first have to shred the paper and mix it with water, and then it comes out as a mash and you can make paper with it. Pulp fiction, the expression comes from the fact that these cheap novels were printed on old waste paper or recycled paper. I find these pictures that are produced with Midjourney, they’re pulp pictures. Basically, you always notice the same motifs: the clone warriors, the sunsets and the beaches… So it works well for things like that. But if you somehow make suggestions that can’t fall back on such an established and popular stock of images on the Internet, then you don’t get much.

Then the next thing you have to think about is that the images are shared, which also means of course, that the big hoover sorts these images in again in the next round. Something like that is a kind of artistic inbreeding, or visual inbreeding. Where certain motifs are thus reinforced more and more by the fact that these hackneyed images are locked up in an endless feedback of more and more boring, hackneyed and devaluated images.

WL: Mhm well, I actually wanted to make these different positions quite clear again. Also what we’ve described here, Harm. If I have understood you correctly, you’ve gone a completely different way and there are artists who do not use any input material in the way we consider it in this day and age i.e. data from the internet, but produce this data themselves. Taking photos themselves or gathering information, which then flows into the systems and so on. That is another level compared to what you have just described.

And the other aspect we haven’t discussed yet is that Harold Cohen developed all his programmes himself. When you work with the so-called AI, in the majority of cases, it is no longer programmed by the artists themselves. They use open source systems, which in the best case, and I can see what you have described, they can simply be adapted through their knowledge and their ability to such an extent that an individual message is really created. Because what you’re describing is, of course, what I see every day and what artists send me every day and describe what great things they’ve done. And I look at it and think, ok, that’s it. It’s really all very similar and it doesn’t replace the vision that an artist must have.

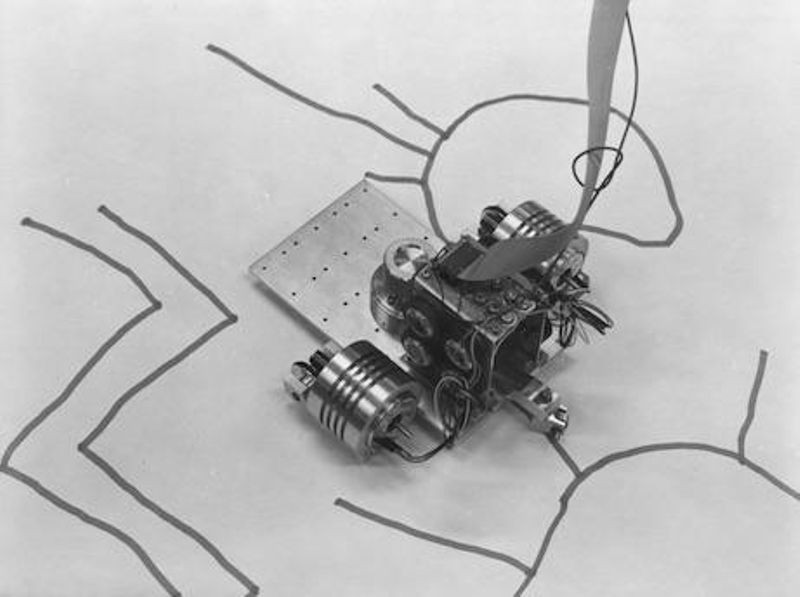

PS: Although Harold Cohen also had a piece of mystification in which his AI had a painter AI. This robotic apparatus. And we can still observe this today, after his death, how the abstract paintings are being painted and it seems to be such an autonomous being.

WL: Do you mean this robot?

PS: Yes, exactly! These small robots that he used. When something moves autonomously, I think that’s when the mystification and mythologization comes in. We observe something that autonomously produces something that looks like an artefact and perhaps looks like abstract art. That’s what I actually found with Harold Cohen. Already at the beginning, where opinions are divided and some say that’s an autonomous painting machine, and others say, as we might argue here, AI is actually just an agent in a larger network. Peter Weibel also said that AI does not exist, but that it’s an emerging phenomenon. An algorithm that needs the energy of the earth, I need hardware, software, I need an artist who wants to do something with it. And then something emerges in this network with this algorithm as an intelligent programme or tool which we define as projection, as artificial intelligence. Something emergent does take place there and, for example, we want to project something into it.

The 1979 exhibition, Drawings, at SFMOMA, featured this “turtle” robot creating drawings in the gallery. Collection of the Computer History Museum, 102627449.

I always had the impression with Harold Cohen when we look at his work, and there are many fantastic stills, where you see how an abstract painting emerges on the floor or where you see his robots. You see him standing next to it and he observes his own handwriting. His personal style is continued beyond his own death. That’s also fascinating, we can perhaps perpetuate ourselves with AI if the program runs forever.

One point about mystification which I found exciting about Harm is… I took another look at his work, which is online on the ZKM website. The parallelism you mentioned with code and cellular automata, in other words, with biology. When artists work and perhaps want to create life-like or variable works of art which develop perhaps quasi-autonomously further. Also with the self-learning principle.

We have something that we can observe, like an evolutionary principle. And there have been parallels in digital art with biology sine the 90s, i.e. with the discovery of the genetic code, with decoding, and we can say that we are also biological automata. Artists too are then natural intelligence, biological intelligences that produce something. But if you try to work with this code, perhaps you can add an evolutionary development to this parallelism of the genetic code, which I see in your pictures, Harm, when one calls them up.

On the website, you have a garden and the abstract pictures develop in such an evolutionary way. Sometimes you’re quite surprised with the results. But then again it’s also my own socialisation, which is sensitive to beautiful pictures. I am socialised in the West, I know abstract art, so there is an affinity or I have a certain preference for certain colour codes. A little bit of Joseph Albers’s principle is still in there, but while you’re watching this process, the way a programme runs in the background and develops immediately, you naturally project something back into it, something autonomous, a living being. Maybe a question for you, the audience can also look this up later and they don’t even have to prompt, you just open the website, the title was somehow with…

HvdD: Mutant Garden.

PS: Mutant Garden! Exactly. Would you perhaps like to add to this parallelism? As an artist, you have written the programme yourself, the evolutionary development, naturally after the tradition of Cohen, and I find that relatively exciting. Because it also has a reflection theme in it, where you think about life, the meaning of creativity, of evolution. How do forms develop through the parallelism of the genetic code with this digital code.

HvdD: Yes, you’ve already said a lot, that’s very good.

PS: I am known for suggestive questions, but nevertheless perhaps the audience is also very curious afterwards and is interested. Because everyone who opens the website gets their own series of pictures. Like you, I can then choose which ones I send to the garden and then let them reproduce on their own. So I find that super exciting. We talk about AI art, this parallelism, which the artist opens up, and then we have a new view of our biology, of human creativity, of life itself, such a reflection. And that is of course much, much more impressive than the broad masses, whom of course also prompt.

But I don’t want to underestimate that all. I know a lot of people who spend a log time on these texts, so a digital ekphrasis is developing there. In the past we had it the other way round, when we sat in front of pictures. We art critics, art scientists, we stood there and tried to put these pictures back into words and now we experience just the opposite. People have to find words for their pictures in their imaginations and the algorithm or the AI model then helps them make them visible. A reversal today is digital ekphrasis.

WL: But these people, I assume, do not generally have a specific image in mind of what they want to create.

PS: It depends, I know many artists sitting here who also work with AI, or Boris Eldagsen who works for an insanely long time in various steps and tries to work man against machine, artist against AI. A very elaborate prompt, so the instruction, the algorithm, that is supposed to give a result, you could almost see it as a sparring partner, like a boxing match. And I find that relatively exciting and I would say AI allows not only co-creation and co-production but also co-evolution in art.

This brings us to the question, do I actually have to be able to code as a digital artist today? My students always ask me: do I actually have to programme today? Is that a skill? Am I illiterate if I can’t programme today? That is the question that is being asked. And if you say that we also need coding skills today, that it’s an educational mandate, then we’re evolving, aren’t we?

Photographer Eldagsen and his work »Pseudomnesia: The Electrician« Photo: Alex Schwander; Boris Eldagsen / dpa

WL: Tilman, what do you think about that? Do we need them? The abilities?

TB: I had my introduction or two topics, but I think they need to be looked at a little more closely. Namely the origin of the images, this feedback that seems to be developing and the other was actually the topic that a lot of these programmes which are used are actually already black boxes. And that of course leads to either the demands that you have to programme them yourself or the question of wether it is generally so desirable for society as a whole to have such incredibly powerful technologies in which unfortunately no one knows exactly what’s behind.

This is a question that goes beyond artificial artistic themes, but that was actually what I found interesting and important about net art. Also as an exemplary model approach, that one could, and back then it was much easier of course, track the black box and make it transparent. And either manipulate it oneself or somehow show the audience, the viewer, how certain programmes work or at least from what mindset they were created.

But that’s an incredibly complex task, Harm said it’s easy to create such programmes yourself, but I personally haven’t yet got into this, it hasn’t really opened up to me. So I’m a bit interested to hear

that from you, as you said you studied it, didn’t you? Also with the ulterior motive of making art with it.

HvdD: Yes, I studied AI at the Vrije Universiteit of Amsterdam, but they weren’t very interested in my paintings. Then I went to the art academy, and they weren’t interested in my algorithms at all. This has changed a bit.

PS: Because new platforms have probably emerged, so maybe we need to think about where this AI art actually takes place. On the one hand, if we now, for example, have artists who work with and about AI, then they are all in residencies, research institutes, ZKM, maybe also DAM. So this is all located in this non-wide art market. The art market is interested in NFTs, which we don’t want to talk about. But there is also a lot of AI art on the blockchain sold at very interesting prices. We have just experienced at Art Basel that there is great interest, because all the tech nerds, the billionaires, they themselves come from a technological background. Now they have a lot of money and they’d rather buy blockchain based digital art.

But of course also new decentralised platforms are emerging on the web. That’s current art which has a suitable community. Harm, your art is website based, ZKM is a website and it is browser based. That means that these are completely new places where AI actually goes. This is very difficult to exhibit in a white cube gallery. We only have the option as a print out no one wants, or on a screen.

WL: Everything is mostly presented on screen.

PS: Most of us don’t have under our radars that there’s a web community, maybe similar to the net art one, continuing with net art, where there’s a further development. The market is a different story.

WL: Yes, that’s a different story.

TB: We’re in an art gallery, why shouldn’t we talk about this?

(laughter)

WL: Before we give the audience the opportunity to ask questions on the subject, I would like to put up for discussion a project which I just discussed with an artist a few days ago. I came back from two conferences about this topic. The artist is Mario Klingemann, relatively known in the field. He’s been working in the field for a very long time, already very early on with concepts such as what is considered AI, machine learning.

PS: He is also a computer scientist.

WL: Yes, exactly. He knows a lot about programming. He developed his own machine learning programme back in 2006 and now of course also works with advanced systems and has created an interesting project. A project called Botto. Do you know Botto?

It’s a project where a so-called AI produces images and these images are produced by prompts and suggestions. A community of thousands of participants choose wether the images are selected as NFTs and which are sold. And this system is running super successfully. The sales are in millions. Now the question for me is, is this still art? What does it have to do with art?

PS: I would say it comes in the creation of the project itself.

WL: When a community decides what the best is?

PS: It is participatory art. But I think it’s the concept and only one person can do it. Only Mario Klingemann can do it. By the second or third person, it gets boring. He was the first to do it and he also did it consciously as an installation which you can observe. Long-term observation, participation with the audience. So you have to look at the concessions to art made by a new generation of young people socialised with social media as art observers. And I would say I find the project very exciting, but who’s pioneer? Who was the first to do it?

For me, it’s a conceptual approach and a slightly ironic one. Because when you talk to Mario Klingemann sometimes, you really notice that he’s a computer scientist and he’s testing out a little bit how things can go. And just to test them and see wether we accept them as art. It’s also a very interesting question, when something shifts in our definition of art. So I see it more as a very exciting long-term project of his. And of course, if you earn well, why not?

WL: He earns next to nothing from it.

PS: He’s not here, we can’t answer that now.

WL: Yes, I did talk to him about it for a long time yesterday.

PS: By the way, on the invitation you sent out, it’s the image in black and white.

WL: The first invitation, I didn’t have a picture from Harm yet so we used an AI work from Mario Klingemann.

Anyway, the community pays in order to be part of that community and to be able to acquire the work. And he’s not part of this community. He is a creator, so he has some shares, but he says what he earns from it is minimal. I suppose such a concept is exactly opposite to how you work, isn’t it, Harm?

HvdD: Yes, but I don’t ask myself this question so often, wether something is art. For me, the question is often wether I find something interesting or beautiful. And about Mario, I think the project is cool but I think the pictures that come out of it are shit.

(laughter)

WL: I don’t think all the pictures are cool, but that’s a different topic. We can all argue about art…

PS: These are the bad paintings…

HvdD: Relational aesthetics, maybe we can call it that. And he is somehow a bit of a troll, by having done all this. Because of course he has a very strong aesthetic sensitivity in his head and he also sees that the images which are created are totally kitsch. But I play along with it and it’s actually very critical so I find it a good project. Wether it’s art? On the one hand probably it is, but the pictures coming out, I don’t find them interesting.

PS: I would actually like to remind you of the wild paintings of the 90s or 80s in Berlin. Those were also bad paintings.

WL: We won’t get into this in detail tonight.

PS: It’s said they’re bad pictures, but that’s just the playing out of this pseudo surrealism that’s coming, which can also be a statement on the conceptual side. It’s the artist experimenting. But for this I only need one Mario Klingemann, and he was the first one, I don’t need the other ones.

TB: I have to intervene now in this „first of the first“ theme. Participatory art and so on, co-creation, that worries me a bit. All these corresponding projects are now obviously no longer so present. But in the 90s, starting with The World’s Longest Collaborative Sentence by Douglas Davis in which all together, people created a text or a sentence and you couldn’t add a full stop. What people found out very quickly, is that they could add a full stop and thus cracked this system. They didn’t only write along. In this case it seems to be about classifying images, I don’t know the project, which is why I wanted to be careful about judging it. But for me it has a consumer feel to it.

With classics in the net art format or Alexei Shulgin, for example, people made their own works according to certain specifications and parameters, which were then shown together in the gallery on a totally equal footing with his own things. As I said, I don’t want to look down on a project I don’t know, but it’s definitely not something new.

Actually, it has to be said that there were much more complex and more challenging art projects online in the 90s.

WL: So you can see the question „Can AI make art?“ is not so easy to answer, but I hope we have been able to give some suggestions. Now I will give you the opportunity to ask your own questions to the participants of the panel.

PS: We can see some artists here, perhaps there will be very critical or interesting questions.

Audience 1: Harm, I would be interested to know which language you use to write your programmes. When it’s not about chance, but about learning.

HvdD: Most of my work ends up finding a target on the internet and that’s why I end up writing JavaScript. But I use TypeScript and I also write WebGL Shaders, so GLSL. And this is quite technical but a bit of Bison, but that’s not that exotic.

Audience 2: Off the top of my head I just remembered that when Photoshop came along, it was also used exuberantly in the field of artistic photography and very quickly lost its magic. Because of course the programme was popularised, anyone can use it today. We can all take magical pictures, but no one is interested in them, and rightly so. Sometimes I ask myself, we can’t all programme yet, but the whole next generation will be able to programme. How will they find this art? On the surface, there is only output. How will they find this output? Because as recipients who only see what comes out, what has taken place on the background is not really relevant. Assuming, of course, that it is a technical level which is about to open up for all.

HvdD: It’s not actually my experience that the newest generation is interested in learning how to programme.

Audience 2: It will happen!

HvdD: I think the new generations have grown up with mobile phones everywhere and everything being very user-friendly. When I started, everything was always broken and didn’t work at all. Technology has become rather transparent and ubiquitous for the new generation.

Audience 2: I’d like to add something from my own experience. When I was studying, we made videos and when it was cold, the tapes would stick to each other and nothing worked outdoors. Now you only need a very small mobile phone and you can make really great, really good film recordings. So I don’t want to attack this, but I see this relationship with Photoshop and artistic photography and other areas, including video that is actually developing positively. These now mysterious things will be available to everyone at some point.

HvdD: The democratisation of resources.

TB: If I summarise it correctly, or part of what you said, you also said that it doesn’t matter what happens behind the surface. But that’s where the power is, that’s where the politics are, that’s where the aesthetic is, that’s where the guidelines are. If they don’t show it, they are really just a user of the programme. They are also subject to the programme to a certain extent.

At least in the early days, I think artists are always interested in such technologies and they also somehow play a special role in that they start to take out the instruments and see what’s underneath the surface. At some point it will be over, but at least at the beginning, when a new technology comes along, artists will roll up their sleeves and see exactly what’s going on in the box. I’m not an art historian, I’m a media scientist and that’s why I’m interested in net art or early video art. And there’s no need for incredibly technical and vivid art. Take Nam June Paik, no one will say he was just a tinkerer. He also established a whole new visual style.

PS: But those are also the exciting AI works of artists, the ones trying to hack or hijack the systems to do something else and point out that monopolies will arise. That the companies are having a huge impact on society and that we are becoming more and more dumbed down by the system. Because there’s so much that remains a black box to us. So if you look at schools, Chat GPT allows you to write texts, pictures are generated without you understanding and there is also a monopolisation. Those who develop programming and tech companies then hold the accounts. That is of course a critical development from a social point of view. If you then say, „I don’t understand any of the code“, then you really are totally illiterate. Today you can perhaps go through the world without learning how to write because you have Chat GPT. That’s the problem.

Audience 2: I think the next generation will be able to programme.

PS: Let’s s hope for it, that it will become the new alphabet, so to speak.

TB: If I’m allowed to stay this, it’s interesting that these Sam Altmans and so on, who are building up the companies, somehow also warn against themselves, against AI, so to speak. But we are never against something like what we were just talking about. They warn about the fact that somehow singularity is emerging on the internet and talking about world domination, completely utopian scenarios lying far in the future.

But it’s precisely this lack of competence in operating the machines and this disenfranchisement, which is also partly due to these technologies that is not an issue for them.

PS: And we haven’t even spoken about biases, i.e. the distortions of reality that are also inscribed in the codes or the data which is used for training. But I don’t want to fall into cultural pessimism, because as I said, I still remain convinced that AI does not exist, as we said, but as a component of a network it is an emergent phenomenon. I.e. intelligent programmes in the tradition of Photoshop. There’s a further increase in the technology of the tool. The instrument becomes more intelligent, has a certain autonomy, apparently, but I should be able to master it, I should understand it, except perhaps at the code level.

You can see that the most exciting works of art are those in which the artist knows about coding and also penetrates deeper so that really meaningful works, which also want to say something, are created. And in the confrontation or occupation with this art, we learn something about our reality, about our present. Therefore, I always understand AI art as art about this phenomenon, or in which AI is used intelligently to, for example, show this parallelism between technology and biology. Or a new art form, new digital aesthetics also emerge. Maybe that’s my addition, so that it doesn’t come across as quite so pessimistic.

Audience 3: My statement doesn’t really fit now, because that was already five minutes ago. But I’ll say this now: I’m a curator, a mediator as well and I specialise in glitch art. Glitch art is not really known in Germany, but internationally all the more so. So of course I see a lot of art and in the end I can only understand the art in which the artist explains the process to me and my appeal to the artists is always: „Please, really, document for me. In two years you won’t remember how you did it, what you trained, which programmes you used. Because art history will only gradually follow in order to understand.“ So there will be a certain lag, a latency.

PS: I find glitch art exciting, but there is also so much mystification. People think an error happens, some bug is in it and a certain aesthetic appears, which also serves as a reflection surface. We believe that something autonomous arises that people no longer understand. There is a whole community about it. I know a lot of computer scientists who instantly grab a screenshot when they see a glitch and are so enthusiastic about it. They project a sort of ghost int he machine. Because at that moment they don’t understand why this glitch is happening, this error in the system. But we have already learned that from Paul Klee, an error in the system, that’s the genius.

Audience 4: So it’s not a question, but a push from the previous thought. Namely wether the next generation will be able to code. I am part of a project called Key Tech, funded by the German government. We tech AI at art colleges and the College of Mainz, for example, is also involved. I teach for the HfG Offenbach, and I notice that people don’t want to code.

So it’s more along the lines of what Harm said. People have grown up with GUIs, ready-made apps and black boxes. Let’s say people who are now starting to study art and are interested in electronic media, also in AI, are unfortunately not very interested in opening up the black boxes and really understanding them. There are always very few people. I think it was the same 20 or 10 years ago in art universities. There were always a few freaks who were somehow up for it. But the problem is that there are many more people who will be forced into these machines and subscription models and will pay money for black boxes which they will use to make art or something else without really understanding all the implications. And I see that as a very dangerous prospect.

It’s going in a direction in which people will use these apps and not change these machine models themselves or code them themselves. So that’s kind of my contribution.

WL: Thank you.

Audience 5: What is your assessment? Does copyright law have to be adopted? Clearly this doesn’t apply at all in the case of generative art, but I mean, copyright law protects works of personal human creation. What is your assessment? How will this be dealt with in the future?

TB: Definitely. That’s already being discussed. I think there’s no way around it. What they did was completely criminal. It’s just like the first internet companies in the 90s or Facebook, these companies got totally out of hand. They did what they wanted and then you actually have to take care of it peu à peu and the AI files of the European Union have at least managed to show the problem as particularly dangerous. It seems to have brought legal requirements into discussion and pass them. But you have to keep thinking about the fact that we are still living with many of the internet’s teething troubles. Any six-year-old can watch pornography on the internet without limits if he or she knows where to look for. All these problems with social media, such as the use or misuse of personal data have still not been properly clarified. And now we have the next construction site where companies appropriate knowledge of the world view and think that this is the basis for their business model.

PS: Tilman, I would like to disagree with you very slightly. I always get a stomach ache in Germany and Europe when people write about regulation. Creativity is now limited to regularity, to regulation, in Germany. This is actually a bit of a pity. You have to think about when it comes to the question of copyright. So there’s three steps: what data material is used? Who wrote the algorithm at the code level? And then, what comes out? So I’d make three sections.

Of course if we go to an art academy, we learn, train our young students or ourselves. We also took everything in. We have looked at Picasso, we have perhaps made van Goghs or drawn nudes. So we have also participated in this culture by, first of all, learning by repeating, training ourselves to then develop our own language or form our own attitude statement which we then want to articulate in an artistic process.

So in this respect, I am also socialised with hip-hop culture. And hip-hop was also an emancipation. I can make use of everything, combine it in new, unexpected interesting ways and create something new. And that is also an act of emancipation. To say: „Do we actually want to? Are we allowed?“ leads us to not being allowed to do anything. Where would you even learn art? If you’re not allowed to look at anything or repeat anything at all.

And then the second level would be the algorithms. That would be a question about the tech companies. Of course they have their hand on it, they don’t hide it either. There are a lot of codes that are not made public, so that stays that way. You can also say that the trade secret is perhaps also copyright protected. If I’m a computer scientist and I’ve written something and it’s an AI model, then I have the copyright. I give it to you as an instrument, like a Photoshop programme.

And the third level, when we talk about regulation, what comes out would actually be initiated by me. When I prompt these are my sentences, it’s my ideas that I want to get out of the machine.

I think that the copyright law or authorship law is becoming more and more problematic and I think it’s a pity and it only ever comes into play when it’s a question of monetary exploitation. So it’s actually a question of exploitation and of course we have a monopolisation, I agree with you. You can see that some people earn a lot of money with it and then authorship is commented on but it’s actually about the money, about earning money. And we won’t get anywhere with regulation.

So then we just pass it on to others, to Asia, to the USA, and we will become a third world country. You can’t say this anymore, so the global north or the other way around.

So I would also differentiate again, but of course I understand your argument, and that people are upset about it and artists in particular have questions. But there is already the possibility of an outtake. There are programmes where I can say as an artist, „I allow the AI to use my photograph, my artwork as training for Midjourney, Stable Diffusion…“ Or like on Google Earth, „I don’t want my house to be shown.“ But then I would have to ask you this question: Where did you actually study? Haven’t you also built up your artistic skills everywhere?

TB: Including a person who is inspired by Peter Kassel or a huge commercial enterprise which somehow wants to raise 100 billion dollars in the next round? Namely OpenAI. These are sums that also existed with all these classic internet companies like Facebook and Google in their most speculative and dark times.

PS: But that is again embedded in economics.

TB: You wanted to actually hear from the artist’s point of view, maybe the artist can talk. But I would like to say something before. I’m not an artist, I’m an author and I don’t know if my texts have been inhaled or not. Probably yes, and it’s not as if I could have clicked somewhere: „I don’t want to be sitting at the other end of the straw when OpenAI comes along and appropriates what’s there.“ What’s that famous quote from There will be blood? „If you have a milkshake, and I have a milkshake…“ I can’t remember, but anyway… If a question is directed to the artist, the artist should have a say in it.

HvdD: Is „Urheberrecht“ the same thing as copyright?

TB: Not quite, but for the purpose of the discussion…

HvdD: I wanted to know of course, when I started with Midjourney and DALL-E, I typed my own name first. And I’m actually an astronaut on all platforms, with a bald head. And that’s good for now. The systems can’t create work like me yet.

I usually publish my work under Creative Commons license with the consequences it has. If a large language model or a Midjourney system takes my pictures and learns from them… I don’t know, in my pictures there are a lot of complex, nested, regressive structures. And these are precisely the things that these systems cannot do. They don’t have loops, and that’s probably still to come. When they do, I will definitely use these systems myself. But I’m not afraid of that, that something will be stolen from me. Because the systems never come up with anything new. It’s always repetition, something stupid and simple, and… they’re welcome to keep doing that.

I also speak easily about this because I have already profited from NFTs in recent years. I don’t have to fight to survive any more. So if someone does something with it, well they should have a lot of fun.

Audience 6: My name is Thomas Schäfer, hello. A lot has accumulated, now I don’t even know where to start. I thought what Pamela said was very good, about the art academy. I also see it that way. The biological intelligence that absorbs influences, somehow generates role models, imitates in the meantime… I have experienced this often enough, that detachment didn’t really work out. Thinking in modules for example, I had a teaching assignment where the whole History was taught in modules. I didn’t experience the young generation, the digital natives, because I only programmed BASIC, I didn’t get any further. Now I have digital natives in front of me, it’s all going to be wonderful, the exchange… And then I also saw that the black boxes were not opened. In video art, where I originally come from, there was no recorder torn open, no delete button removed. I started with it, it didn’t interest me at all.

My hope is also my question, about the prompts. A friend of mine who has been working since for ever for Google & co. and the AI he trained there. Things were described for it, so it’s the other way round. The prompt, as far as I understood, comes back with certain blurs. As an artist, I am now interested on AI as a source of inspiration for my patterns and actually interested in glitch. Very briefly summarised, sometimes quite nice things come out, which make me think of cool decorative art I have often seen in galleries, but my hope is that AI will somehow eliminate decorative art. That perhaps so much is made of it that the buyers, the art scene, the art market, the gallery owners themselves and the artists get sick of it and don’t want to see it anymore. And that everything turns more to concept.

Because I have the feeling that they hardly listen to me when it comes to concepts. Sometimes not even believed in because it’s a thing that falls out of the grid. And I have the hope that the AI, the pseudo AI maybe, builds up such a pattern in a direction that backfires.

TB: Was it a question or a comment?

WL: Both!

TB: I’m afraid you can’t underestimate the consumers. If you look at how culture has developed, another superhero film, who knows how many Spidermans, Harrison Ford being resurrected and playing treasure hunter again… Somehow we’re living in a phase of cultural history where everything seems to go round in circles. And I don’t see any great counter-development at the moment.

Now you can say that AI is overloading the system in such a way that will eventually tire out even the most patient people, but this point hasn’t been reached yet.

PS: But everyone in art and aesthetics is waiting for the AlphaGo to make a certain move, the moment when people will say „Humans haven’t been able to think about this yet.“. That you make this move and then win the game. We just have to admit that the computer performance naturally exceeds biology. Every calculator is better than us.

Of course we will also find patterns in computing power. I’m also the opinion that AI art is also meta art, because it somehow shows us something from our data. Pattern recognition is a big issue at the meta level, it says: these are the trends right now. With Midjourney, suddenly after the Russian attack on Ukraine the images darkened because the internet was flooded with war images. And of course the AI immediately learned and the colours got darker. That was such a meta observation. So I say the AI model reacts to our input data and you can experience it in real time on a meta level. Suddenly war images are virulent on the internet and there are certain events, peaks. I think AI is a good tool for data visualisation and it recognises this kind of thing because of the computing power that exceeds our brains in the meantime. Patterns which we would need a long time to find. And on that level, I think some artworks which work on this meta level and not just to hack the system are very exciting.

We could name Refik Anadol. Some say it’s a beautiful lava lamp. He said he used quantum computers to visualise the MoMA, all the abstract art works into a flow. I would say it’s data visualisation, wether you like it or not, and you have to believe what he says. There’s the black box again. So is everything actually true? The quantum computer is right, the code is right, and then we realise we’re becoming illiterate. There is a dangerous gap in society where there are people who are tech nerds and geeks and have mastered these codes and are also earning a lot of money because they have start-ups and are economically supported by certain countries where there is no regulation. And then there’s us, who only have accounts which we also have to pay for. OpenAI, Tilman already said this, earns a lot of money and we only use these tools like monkeys and are happy to get a few nice pictures.

That’s why the art scene is so important. Art has to deal with this contemporary phenomenon and this technology. And with some AI artists, here is one sitting in our midst, we learn a lot about life, about evolution, about forms, education… And for such things it’s a good instrument. It is the same question as with a knife: can I kill someone with it? Or can I peel my apple? So the question is what I want to do with it and how do I master it. Do I have skills and abilities to deal with it?

And of course that becomes more complex because the AI models are very demanding. Either you are involved in co-evolution and try to understand this system and help shape it, or you are left behind and that is of course a bit of a danger. If I don’t understand anything anymore then I don’t need to learn how to write at school because I can ask Chat GPT and I get a text, pictures…

So on the one hand there’s artificial stupidity and on the other hand there are people who are clever and say: I want to understand it, I want to use it, I also want to help shape it. The future is shaped by us, we decide it, it’s not something that comes to us. Since that sometimes requires a bit of effort, I have to say, ok, I have this new technology in which the question is how technologically supportive we still are. Do we really want it? And if some people go ahead with it, there’s the danger that some will be left behind. That’s just the way it is, sorry.