An Emergent Paradigm

Paul Brown

Lessons unlearnt

It’s reported, athough probably via apocrypha, that Michelangelo was advised by his contemporaries not to use stone as a medium. It was not befitting an artist who should, of course, have been using marble. Three centuries later the Impressionists were reprimanded for using paint from tubes because, as everyone knew, artist grind their own pigments in order to create a personal palette. By the early years of our own century we find the Constructivists being criticised for using modern industrial materials like plastic and steel and reminded that real artists used stone. Duchamp and Schwitters were just two Dadaists who were scathingly attacked for their use of found materials instead of paint out of tubes like the more commendable of their colleagues.

The lessons of history seems plain: the art mainstream is hideously reactionary and beware any creative soul who experiments beyond the boundaries they prescribe.

For the past 25 year computers have been the forbidden medium. It was OK for established artists like Warhol and Hockney to use them but for a young unknown it was the kiss of death.

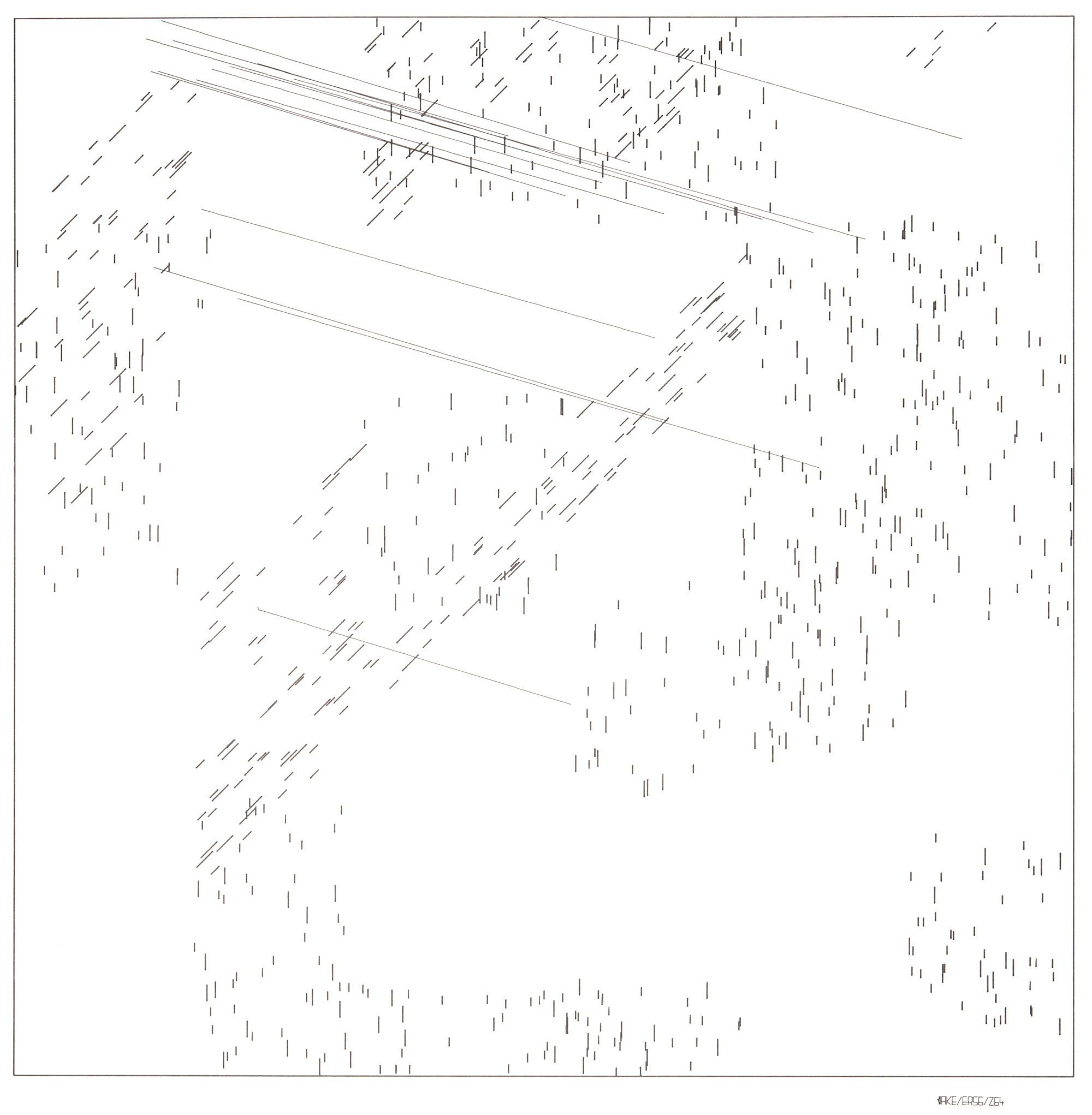

In the mid 1970’s I was a emerging artist who had picked up a few important awards and commissions. I was introduced to a major critic who could … “do my career a lot of good”. He spoke glowingly about my work until I made the mistake of mentioning the involvement of computers. “You mean computers do this?” he asked incredulously. I hadn’t mentioned the fact earlier because the drawings were quite obviously produced on sprocketed computer paper that had the Calcomp logo repeatedly printed down one seam. “I thought there was something cold and clinical about the work”, was the critics parting comment.

Twenty years later, almost to the day, I recently won the Purchase Award in the Shell Fremantle Print Award. Although the winning piece has attracted some fairly reassuring praise it has also been described as “cold and clinical”.

Lapses in logic

In his essay “Art and the Net – A Lay View” in the August 96 issue of Periphery Jacques Delaruelle reasserts the conservatism of the academy. Although he puts it differently he means the same thing:

“What is missing” from the digital artwork “is the involvement of the body, a texture, the weight of things, the natural life in which they bathe and with all these, the quality of attention necessary for a text or an image to be seized and then transformed by the imagination.” (This authors words in italic).

Later he goes on to say:

“Little time has been devoted to the question of what is actually lost in the digitisation process”.

His meaning is clear, the digital, or computational process is defined as a destructive process by the use of the word “loss”. For Delaruelle, this process has no role in “creative” activity.

It would be petty of me to highlight all the logical discrepancies in Delaruelle’s text but his use of the word “digitisation” is symptomatic of the fallacy of his argument. Digitisation goes back well beyond computer technology and, in the form of half-tones, is the main way that images have been reproduced in print. The original continuous tone image is sampled (in the pre-computer days using an optical filter) to produce different size dots of solid colour ink that the eye merges and, by so doing, reconstructs the continuity of tone of the original.

This kind of digitisation is acceptable to Delaruelle:

… “it” is “difficult for me to believe that one can `read'” … “a digital image in the same way one looks at a printed” that is to say – digitised “image”. (This authors word in italic).

As any student of philosophy will be aware we are now in dangerous territory. A distinction has been drawn between one state and another where the “naming” or “placement” of the distinction is ambiguous. As Spencer Brown makes clear in the opening definition of his masterwork the “Laws of Form”:

“Distinction is perfect continence.”

Lest there is any ambiguity he comments further:

“Once a distinction is drawn, the spaces, states, or contents on each side of the boundary, being distinct, can be indicated.” (1)

Delaruelle’s distinction is incontinent and it pretty soon becomes clear that, rather than stating an defensible position, he has, like a politician in retreat, resorted to the use of broadband rhetoric to protect a prejudice. He doesn’t like art that involves computers. His opinion can be summarised in just seven words.

Beyond the gilded frame

Readers may now be surprised to learn that I agree wholeheartedly that so-called computer and network art, with few but notable exceptions, exhibits a dire lack of value. I’m even game to include most, if not all, of my own work in that category. However I am quite convinced that the computational metamedium is the future medium of choice for the arts. How can I justify such optimism?

The internet began in the 1960’s as an attack-proof communication system for the US Defence Department. Soon afterward artists like Roy Ascott (in the UK); Carl Loeffler (founder of ArtComTV in San Francisco) and Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowicz (founders of the Video Cafe in Santa Monica) began using telecommunication systems. Galloway and Rabinowicz’ “Virtual Space” (1977) is typical. Two groups of dancers, one on the USA’s East Coast, the other on the West, were able to perform together via bidirectional satellite links and video compositing and projection tools.

In the 1980’s the “Aesthetics of Telecommunications” group was founded by Fred Forest and Mario Costa. Earlier this year Australians had the opportunity of seeing the work of one of their members when Stephan Barron exhibited at the Adelaide Festival (2). Despite equipment problems which closed the show early Barron exhibited two works.

DAY AND NIGHT used the internet to link Adelaide with a gallery in Sao Paulo. On the roof of each gallery video cameras pointed at the sky. The digitised images were communicated to each other site where they were mixed and displayed. The two cities are 12 hours apart – as the sun sets in Adelaide it rises in Sao Paulo. The exhibited images were a dynamic mixture of the sky at day and night.

In OZONE the Adelaide gallery was linked to Paris. In Adelaide the atmospheric ozone hole was sampled, in Paris the ozone in car exhaust fumes was digitised. Here again the internet transferred data back and forth and it was used to “play” prepared pianos.

Art-Reseaux (3) is an international group who’s members began using fax communication. In 1992 in Paris I saw documentation of one of their events. Two fax machines were linked with a single loop of paper. One sending, the other receiving. The loop of paper travelled between the machines over a table where participants drew and collaged onto the surface. The result was sent to another international location with a similar setup. And so on until the faxed image returned via the receiving machine in Paris. It was a digital “orbit” of the planet.

Works like these (4) evolve from the experimental art of the 1960’s and help undermine the modernist aesthetic of “intrinsic” value and the “grand narrative” of the gilded frame. Artworks become valueless and their relevance is as a signifier, their content becomes extrinsic dialogue and interpretation.

User Friendly – a metaphor for the past

In January 1994, the internet was popularised by a user-friendly “browser” called Mosaic. Soon millions of affluent first world citizens would discover that it was just as easy, and cheap, to create their own publications. It was vanity publishing gone mad.

User friendly interfaces use metaphor in order to work. Their message is simple: you don’t need to learn anything new to use this software. Digital Darkroom software mimics real chemical and optical processes. Illustration packages imitate technical pen and french curve. The metaphor is clearly to the existing, established paradigm.

And so Mosaic, and the Netscape empire it spawned, reinforces and mimics the printed “page” and architectural “site”. User friendly interfaces have broadened the franchise and are egalitarian but at this cost – they reinforce the past at the expense of the future.

Instead of promoting the computational metamedium as a new and unique potential for the arts they have straight-jacketed it into the current media paradigm. And here is the source of my, and I’d like to suggest Jacques Delaruelle’s, discomfort. The medium is pretending to be something else and, like most charlatans, it can’t carry off it’s pretence and leaves its audience unfulfilled.

So the World Wide Web has reinforced modernist concepts of the gallery, the virtual gallery, as a place for revering and monitarising artworks. It’s re-established the idea of art with intrinsic, self referential values and compromised the idea of art as extrinsic signifier.

So now it’s postmodernism that’s undermined. Perhaps deservedly considering the idiot fringe of some of its rhetoric and the poor understanding of many artists who mistake its dialogue for an excuse for indulging in romanticism at its worst.

A historical model

I have been searching for historical models since user friendly interfaces first commercially appeared in the early 80’s. I was aware that the work produced before then (using difficult programming methods) had a greater sense of integrity and wanted to know why?.

The development of the wet plate process by Daguerre and Fox-Talbot was followed by a forty year hiatus before the portraits by Margaret Cameron establish a unique photographic aesthetic. In cinema the invention of the motion picture transport by the Lumiere brothers in France and Edison in the USA needed a forty year transition before `Russian montage’ evolved and the language of cinematography matured.

In the early days of photography artists made pastiches of their academic paintings. In cinema the camera was pointed at the theatre’s proscenium arch and the action was filmed from the audiences perspective. Improved lenses allowed close-ups then conjunction by montage, or editing, completed the `grammar’ and the new language was, essentially complete. We watch feature films of the mid 1920’s and see complete works that are in essence little different from today’s cinema narratives.

Now we see new media being used to mimic traditional ones. Are we within a 40 year process and, if so, when is it likely to come to term?

Why forty years? Can this period be reduced? This question worried me for some time until my youngest son, Danny, came to stay for a year. Now 19 Danny has never know life without computers. He’s extremely competent with them and, most recently has worked as a web and multimedia designer. Danny has now returned to the UK to study art and technology with Roy Ascott at Newport College of Art. He’ll be emerging as a new talent in his mid 20’s – around 2002. Then it clicked. John Whitney Snr. became the first artist in residence at IBM in 1962 – 40 years earlier. The phrase `computer graphics’ was first used that same year.

Forty year is precisely the time it takes for the technology to mature and, more importantly, for a new generation of artists to develop who haven’t been influenced by the previous paradigm. It would seem that this can’t be condensed. Forty years is it.

Somewhere in the middle years of the next decade we should begin to see a new language, a new aesthetic, a new paradigm emerge. Can we possibly foresee what form it may take?

Consulting the oracle

Brenda Laurel warns against attempts to predict the future (5). By doing so we may prejudice it’s evolution.

It’s also very difficult for someone who’s emersed in the current paradigm to see a future change particularly when that change threatens the accepted wisdom of the status quo. In this sense the future is the enemy. Impressionism would overthrow the 19th century academy and their criticism of impressionism is symptomatic of their distress at the immanence of their demise. That this perception was possibly subconscious is irrelevant. The new paradigm is like a stranger with a loaded gun that’s pointing at your head. To make them welcome is tantamount to suicide.

Here again history teaches us that the new is almost inevitably rejected by the holders of the status quo. My favourite example is Schwitters. Today his work seems quite tame and “tasteful”. However the contemporary record shows just how confrontational it appeared to his contemporaries and how viscously he was reviled for his use of found materials like the bus and tram tickets which he picked out of the streets of Hamburg.

Thanks for the signpost

If we want to watch the new aesthetic evolve we should perhaps look into those things we like the least, those things which affront our sensibilities the most. It’s there, most likely, that the foundations of the new language will lie.

And it’s here, perhaps, that we can recognise the true value of Jacques Delaruelle’s article (and those of the many other detractors of the new media). It points to a place and reassures us that the computational metamedium and telecommunication process, by being so reviled, are almost certain to become a part, at least, of the future paradigm. What artists will be doing with them is anyone’s guess.

References

Spencer Brown, G., The Laws of Form, George Allen and Unwin, London 1969.

Brown, Paul, Stephan Barron, Catalogue essay for the Telstra Adelaide Festival, April 1996.

O’Rouke, Karen (Ed.), Art-Reseaux, Editions du CERAP, Paris 1992.

for more examples of telecommunication art see: Popper, Frank, Art of the Electronic Age, Thames and Hudson, London 1993.

Laurel, Brenda, A Taxonomy of Interactive Movies, New Media News, Vol. 1 No. 3, 1989.

Periphery

This essay was commissioned by and first published in Periphery No. 29, November 1996. Periphery is an Australian quarterly regional art and craft journal which includes a regular focus on indigenous art and craft.

Paul Brown is an artist, educator and consultant.