HAROLD COHEN

UNIQUE

Remarks on the opening of the exhibition

at the DAM Gallery Berlin, 25 January 2019

Frieder Nake

Wouldn’t each and every one of us gathered here, whose mind and hand perhaps reach for the artistic, eagerly wish to be represented with works at the documenta in Kassel and, on top of that, in Venice at the Biennale?

Harold Cohen was represented at documenta 3 (1964) and soon afterwards at the 33rd Biennale (1966). Born in 1928, he was in his mid-thirties at the time. He came as a painter and representative of the United Kingdom.

But Harold Cohen appeared a second time at the documenta: at the sixth in 1977. He now came as the companion of a Turtle, if we take the word literally. It crawled around on the floor more badly than well, guided by a long leash through which it received signals that determined its path. The signals came from a computer and the Turtle, following the signals faithfully, left traces on the large sheet of paper placed underneath it. These were drawings that the master himself affixed to the wall of the exhibition. He wanted to, and did, colour them in by hand according to his own will and taste.

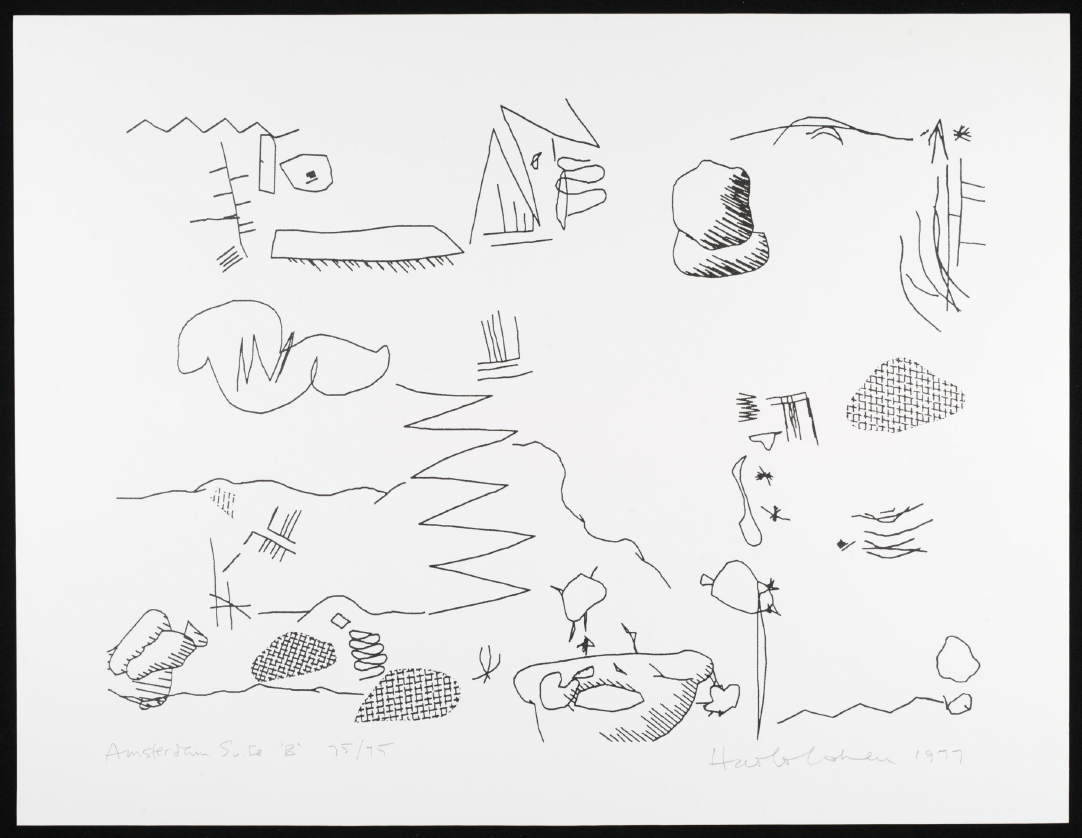

As far as I know, nothing that Cohen’s automatic painting box, the Turtle, was able to draw during the hundred days of documenta 6 in 1977 has survived. He told me that he was not overly satisfied with the situation in Kassel. There were too many technical problems to overcome. The big show took place from 24 June to 2 October. Cohen packed up his things and machines and moved on to Amsterdam to the Stedelijk Museum, where people usually make a pilgrimage to marvel at Rembrandt’s art, which has survived for several hundred years. There, from 25 November 1977, the good Turtle was once again shown in action. It had to keep up until 8 January of the following year. Cohen liked it better in Amsterdam than in Kassel.

After that, however, the Turtle gradually became too much for Cohen and he set about getting rid of the lively little drawing box. He had noticed that the public’s interest was more focussed on the drawing turtle than the drawing result. The movement that leaves traces is more fascinating than the configuration of the traces.

Cohen had a similar experience several years later. It led him to rethink his techniques and procedures. The AARON programme system, which he had developed during a guest residency at the Artificial Intelligence Lab at Stanford University (1973 to 1975), had enabled him to produce portraits automatically in the mid-1990s. Cohen was not interested in having a living person portrayed automatically, as is demonstrated here and there today by robotic devices. Rather, Cohen had developed his system of drawing and painting rules, which AARON had to follow, to such an extent that it could produce images of the “portrait” genre: imagined portraits, if you like. No-one has attempted this, no-one has got this far with a system of formal rules. The so-called expert systems were once a bloom from the diseased swamp of computer science, praised above and beyond the green clover with expectations, promises and predictions. It withered away because the euphemists had overlooked one thing: The knowledge is not extracted from the experts by a few smart youngsters who have been quickly turned into knowledge engineers in such a way that it can be placed on the table in handy data form. Expert knowledge is to a large extent implicit knowledge. As such, it lives in the expert and makes them into one.

In Harold Cohen, however, we have an expert who asked himself questions and who formalises what he is interested in himself. This is why his expert system AARON was able to become successful without being stylised as such. Until Cohen switched it off for completely different reasons. For the reason that he considered what it did masterfully to be irrelevant to art. A unique process in its genesis and its cancellation.

“Think the pictures, don’t make them!” is an appeal to algorithmic art that has become dear to me. Harold Cohen thought quite differently, but with the same result: “Think the pictures and then perhaps don’t let them be made!“

As always, Cohen was keen to introduce AARON in action to the audience. Conversely, the audience was delighted and grateful to see the machine painting. It was now working with a brush-like instrument, creeping up to the paint pots, to one in particular, dipping the painting instrument into the colour, letting the excess drip off, wiping it off and painting unerringly with a style reminiscent of Photoshop’s smooth surfaces at the very least. Fascinating for anyone who saw it! Another aspect of this artist-constructor’s uniqueness is that he built his drawing and later painting machines himself (first painting machine in 1995).

In fact – that was the problem again. Because seeing such a machine (constructed by the master himself!) in action was very much to people’s taste. Was this the painting, the upcoming art? Well, not necessarily. The process of making it was probably more exciting. (I may mention that I wrote an essay in 1985 entitled: “What is more important: process or product?” The question was addressed to algorithmic art).

Harold Cohen made a radical change: at the beginning of the 2000s, he broke off his affair with figurative art and returned to the lines and forms that had always interested him in an abstract (or really: concrete?) way. He had, as he now thought, lost his way. He pushed the system of rules to one side and collapsed it into algorithms!

Volume 3 of the extensive documentation of the works shown at documenta 6 is dedicated to hand drawings, utopian design and books. When I open it, it cracks and crackles: it is falling apart, this 42-year-old tome at the time of writing. No wonder, given the lousy binding of such a heavy book. Loose leaves fall towards me and the small, pale font calls out to me that I should perhaps buy stronger glasses for reading. But I don’t like that.

The “Hand Drawings” section is divided into nine parts. They are chosen more or less compulsively, more or less arbitrarily, sometimes bringing together many works, sometimes only a few. The ninth section is devoted to “Drawing Machines”. Only three positions appear, almost a small cabinet of curiosities: Harold Cohen, Rebecca Horn and Jean Tinguely. They are given no more than four pages. Horn has strapped a spiky pencil hedgehog to her face and head and is waving it around on a piece of paper close to the wall as if she were a machine. That’s what we’re supposed to think, because why else is she with the drawing machines?

There is one of Tinguely’s early funny-looking rattling mechanisms, screwed and welded together from scrap metal, which scribbles cheerfully on a small piece of paper. Since 1955.

Harold Cohen is different. He has fenced off a large area on the floor. An impressive paper surface

lies ready. In the photo (below) we can already see some drawing elements on it. The computer stands in the corner. Five adults, three children in the room, a little shy, all of them too well-behaved for my taste today. A young man leans over a monitor on which we can surmise messages from a working computer. A slender young man leaves the room. Outside, drawings of AARON, hand-coloured by Cohen, await him on the opposite wall. If the young man above the monitor tries to explain something – will people have understood it in 1977? When you’re young, you don’t necessarily want to be understood.

AARON is still in its infancy. Harold Cohen has been working on him for four years. He has set out to understand the open form and the closed form. We know from the exhibition at the DAM Gallery that he has been successful. A rich treasure trove of such forms leaves its trail as a trace of the turtle held on a long ribbon. A fascination and nothing but the constant question: how does it work, how does it do it? We don’t know the answer. We still don’t know the answer today, now that 42 years have passed! Isn’t that shameful? Are we not learning anything? Don’t we need to understand anything?

Harold Cohen is regarded as the first artist whose new, never-before-seen works will still be available long after he dies. Because the system can continue to work without him. A nice thought. He didn’t mean it entirely seriously. He shouldn’t have done that. Because of course that can happen with the new works after death.

By chance, while rummaging through my clutter, I came across a sheet of paper with perforated pages, from the telex machine. On it, only in German and worded a little differently, was a similar message about the new works after death. In the summer of 1964, I had stuck a few drawings of the SEL ER56 computer and the Zuse Graphomat Z64 drawing machine on the wall of the computer centre at Stuttgart Technical University. Among them was the assertion about art after death. If we in the algorithmic world think the pictures and don’t make them, then something like this will emerge. With necessity.

When Harold Cohen could no longer, as he thought, see through the system, which had grown to 300 rules, to all the effects caused by adding a new rule, he pushed the rules to one side and concentrated on the algorithms that generate the shapes. Colour, he decided, could not be mastered algorithmically beyond the trivial. During his last period, he left the forms to the machine and concentrated on colour again, his actual profession.

When he could no longer stand in front of the rulings and draw into them, he got himself a huge screen with a touch-sensitive surface (touch screen). He and his assistant Tom Machlik managed to get Harold to select a colour on the screen of the computer that was part of the system. Sitting in a wheelchair, he could then use his finger to colour areas and lines on the screen. The colour stuck to his finger digitally, i.e. invisibly. He became a finger painter again, just as he might have been as a child.

A huge circle closed for Harold Cohen towards the end of his life. At the age of 38, he had reached the pinnacle of his career as a traditional painter who loved colour. From 43 onwards, he was only concerned with the tension between algorithms and aesthetics. By the time he was around 70, he had done more than anyone else and turned his back on the system he had created. Not to withdraw from the calculable or even from the image. He returned to the simplicity that lies in the algorithmic. He was very fond of artificial intelligence at Stanford and for many years afterwards. As far as I know, he did not explicitly abandon it. He did in his actions.

What we can learn from Harold Cohen is unique. He was someone who always thought and acted radically, an erratic block on the coast of the Pacific. His radicalism was always friendly. Don’t we want to be like that too?

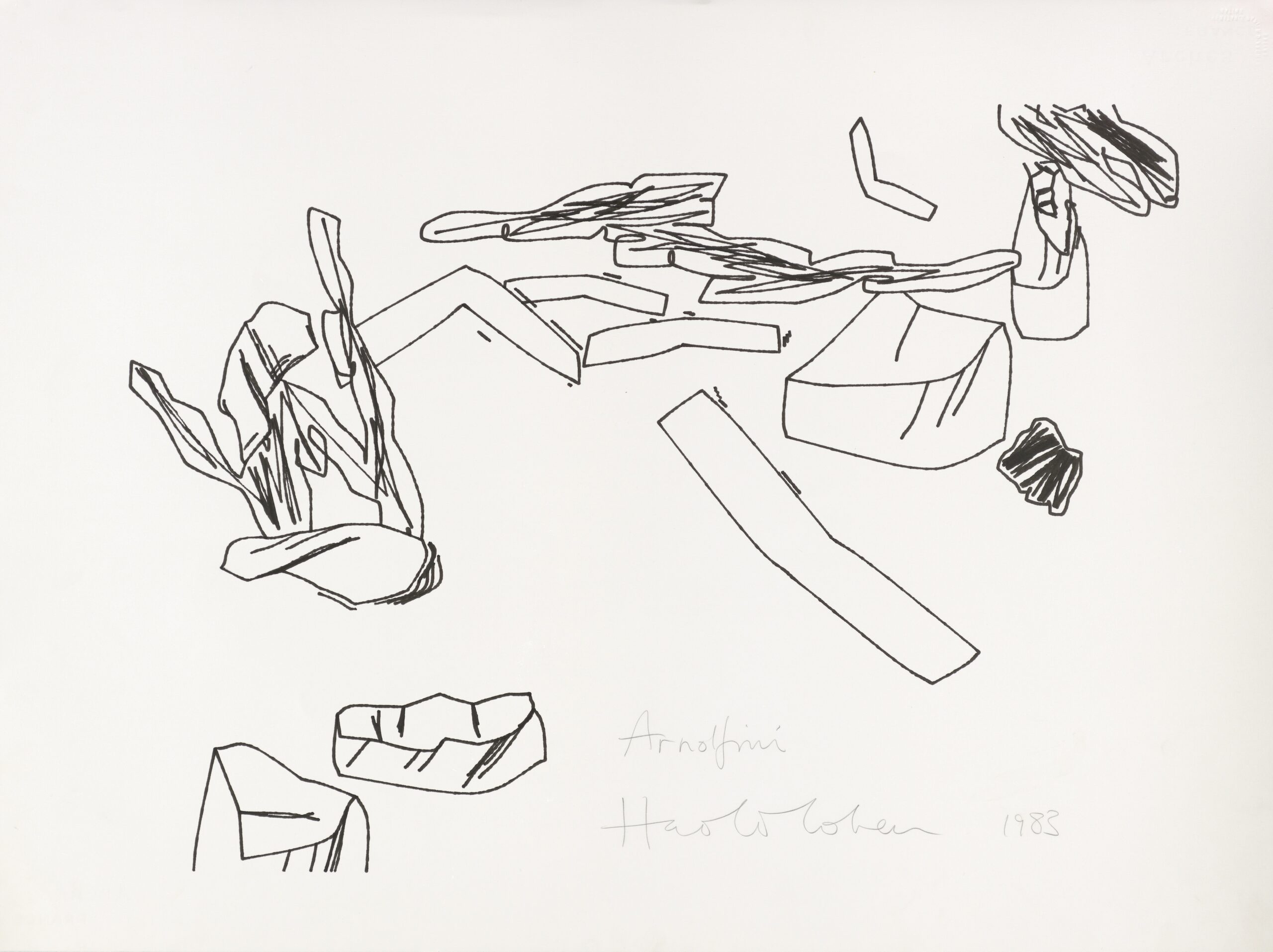

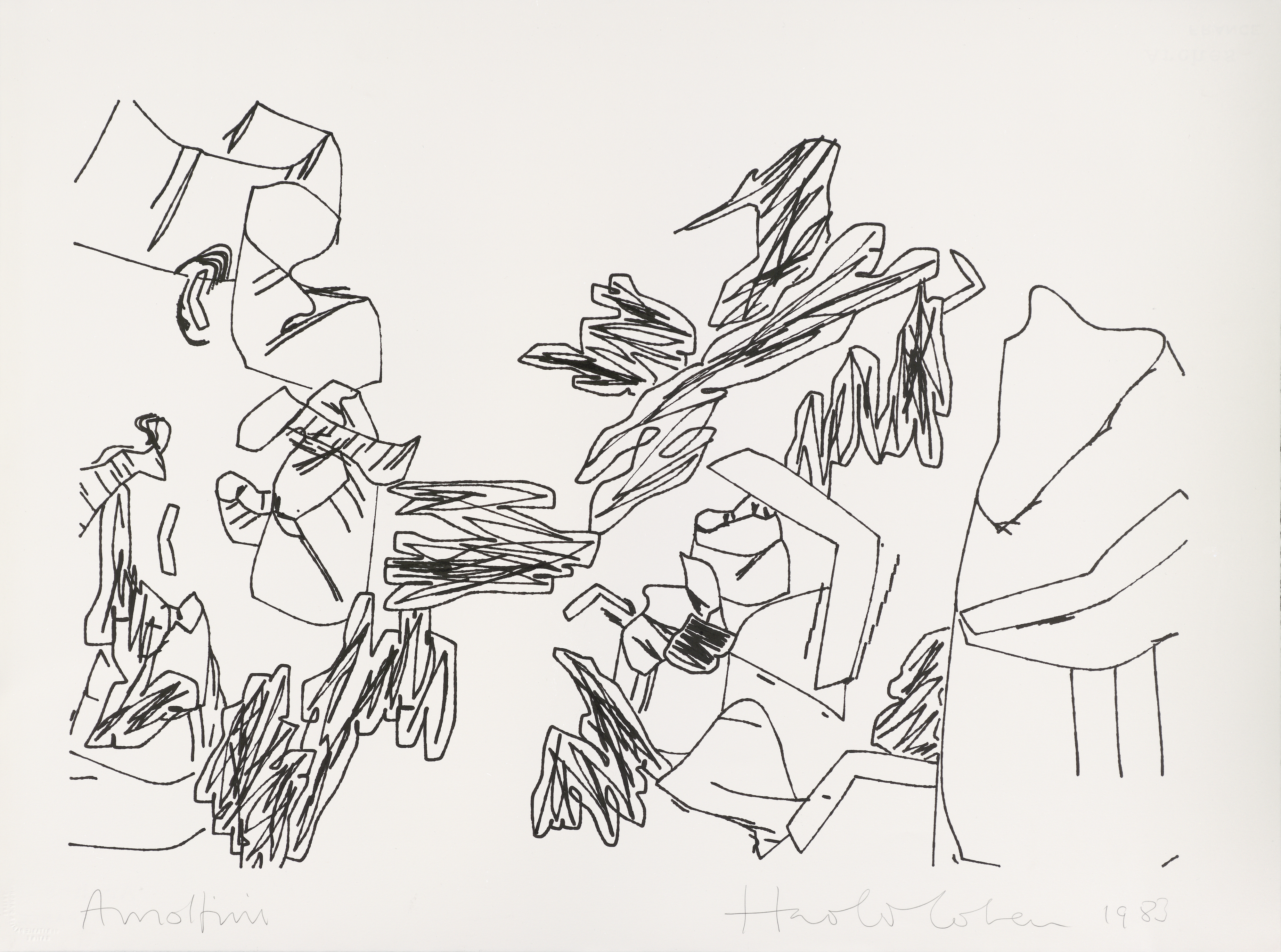

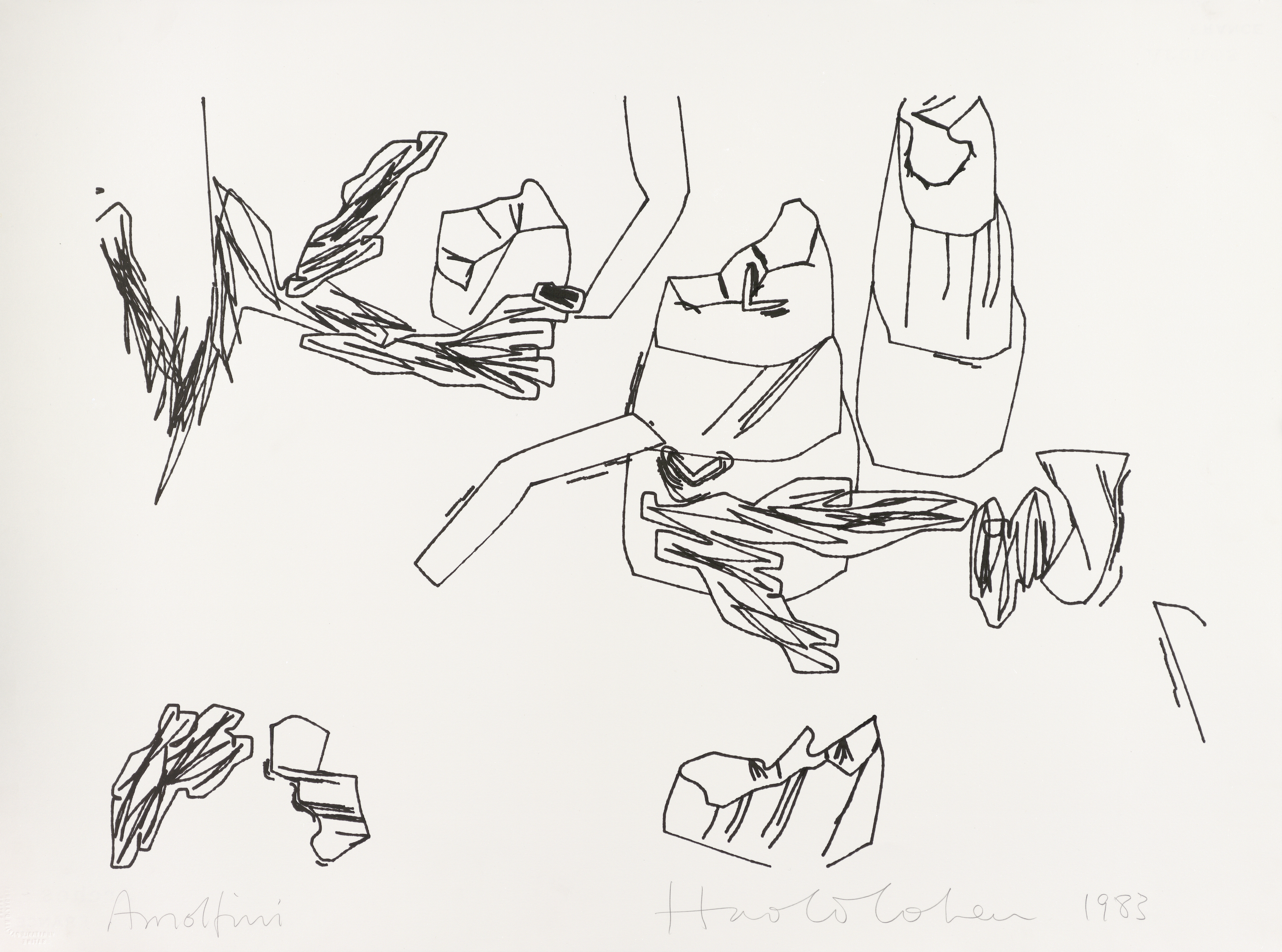

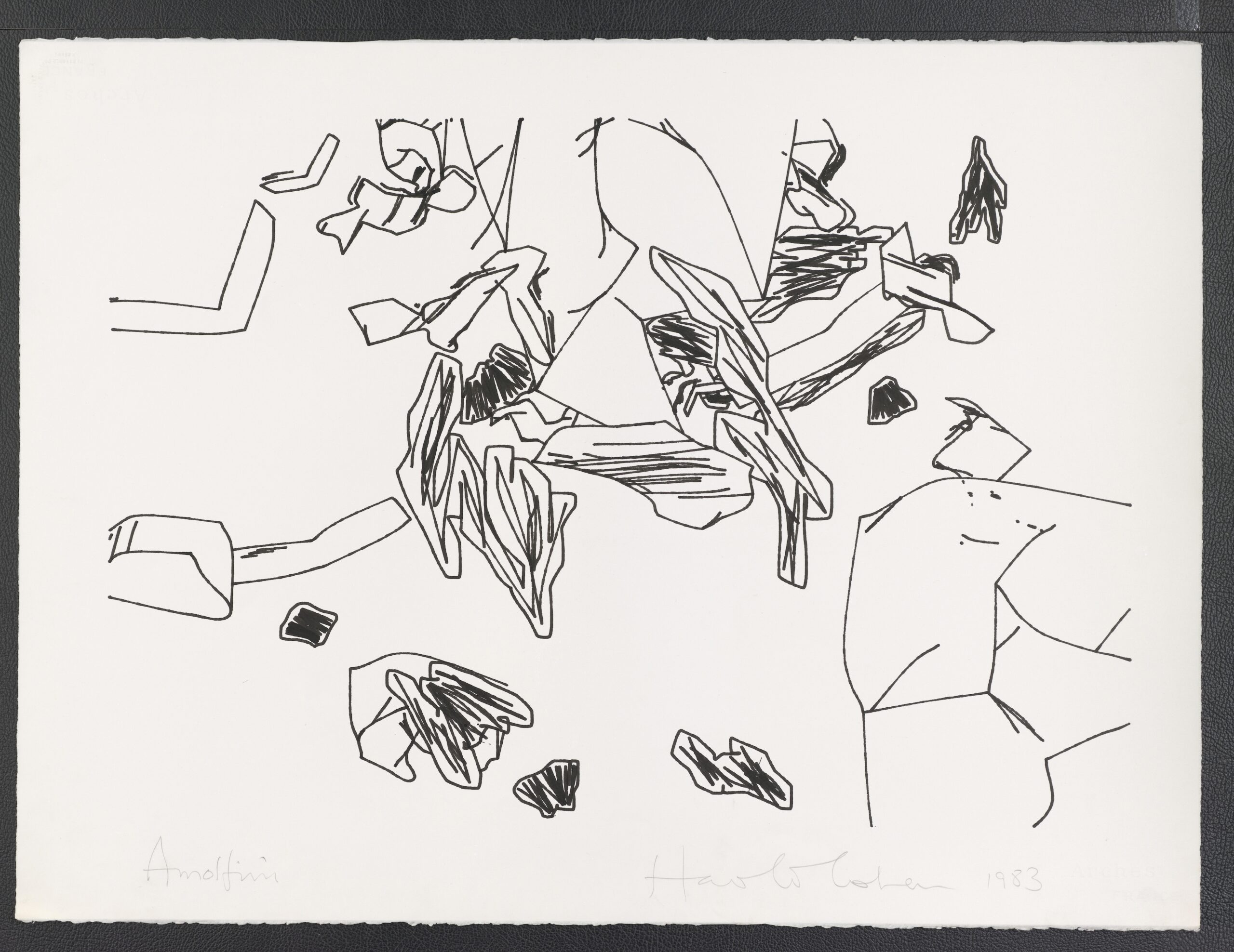

The exhibition “Harold Cohen” shows drawings that he exhibited at the Arnolfini Gallery in Bristol, UK, in 1983. At that time, AARON had not yet begun with figurations. The pictures can be seen at the DAM Gallery Berlin from 26 January to 16 March 2019.

Postscript. When, after a considerable delay of five weeks, I wanted to start formulating the promised text from my Berlin lecture notes, these, which I had deposited in a black notebook, which I have been using for years, had disappeared without a trace because the book itself had disappeared. Anyone who keeps such a book about their work, about what they feel is important to record, knows what it means to lose six months’ worth of notes. I can’t explain it to myself. However, I have to assume that the traces of about half a year of my existence have hurried off on some train after I left it. Readers looking at the above lines should therefore bear in mind that almost nothing of the formulations I was tempted to use on 25 January 2019 at the DAM Gallery in Berlin can appear here. But there are worse things under the blue skies.