Hearsay and early telecommunications art

Norman White interviewed by Pau Waelder

May, 2021

Hearsay (1985) was Norman White’s first telecommunications artwork, a 24-hour event based upon the children’s game whereby a secret message is whispered from person to person until it arrives back at its originator. White chose a poem by Robert Zend, aptly titled “The Message,” to be the text that would be sent over eight different nodes in the IPSANET global computer network, each time being translated into a different language, and finally coming back to its origin, re-translated into English, its meaning obviously transformed by the successive interpretations of human translators. This event exemplifies the growing interest in telecommunications networks by artists working with computers in the 1980s, alongside influential projects such as Robert Adrian’s The World in 24 hours (1982), a networked happening organized by the Ars Electronica festival in Linz that connected sixteen cities worldwide, or Roy Ascott’s La Plissure du Texte (1983), a fairytale narrative distributed among nodes across the world. White would later create with artist Doug Back another seminal telecommunications project, Telephonic Arm Wrestling (1986), which used a telephone link to connect two motorized devices, one in Paris and the other one in Toronto, allowing the artists to establish a direct, haptic feedback system between the two distant cities.

In this interview, Norman White explains the creation of Hearsay and the context in which him and other artists were working with early computer networks.

Before Hearsay, you had been working on different types of robotic installations, what drove you to work with telecommunications?

I have a good friend, named Bob Bernecky, who worked for IP Sharp Associates, otherwise known as IPSA. It was the Canadian computer time-sharing and consulting firm that had customers who worked in finance and were Toronto Stock Exchange clients. As such, IPSA had communication links to centers all over the world. There were offices in about 50 cities, mostly in Europe, including Amsterdam, Frankfurt, Zurich, Milan, Copenhagen, Vienna, and Dusseldorf, but also offices in Japan, Australia, Canada, the United States, etc. Their communication links were largely used by engineers who were coordinating their efforts to make sure that the data flowed smoothly. Bernecky said to me: “You know, there’s a programming language called ‘APL’, which stands for ‘A Programming Language1 that you should try out because it’s really powerful.” [1] Now, APL uses all these weird symbols and even though I was smarter then than I am now, I was not up to mastering them. After a few tries, I decided it was a waste of time. However I was not put off by IP Sharp’s system itself because of the communications tentacles it had all over the world.

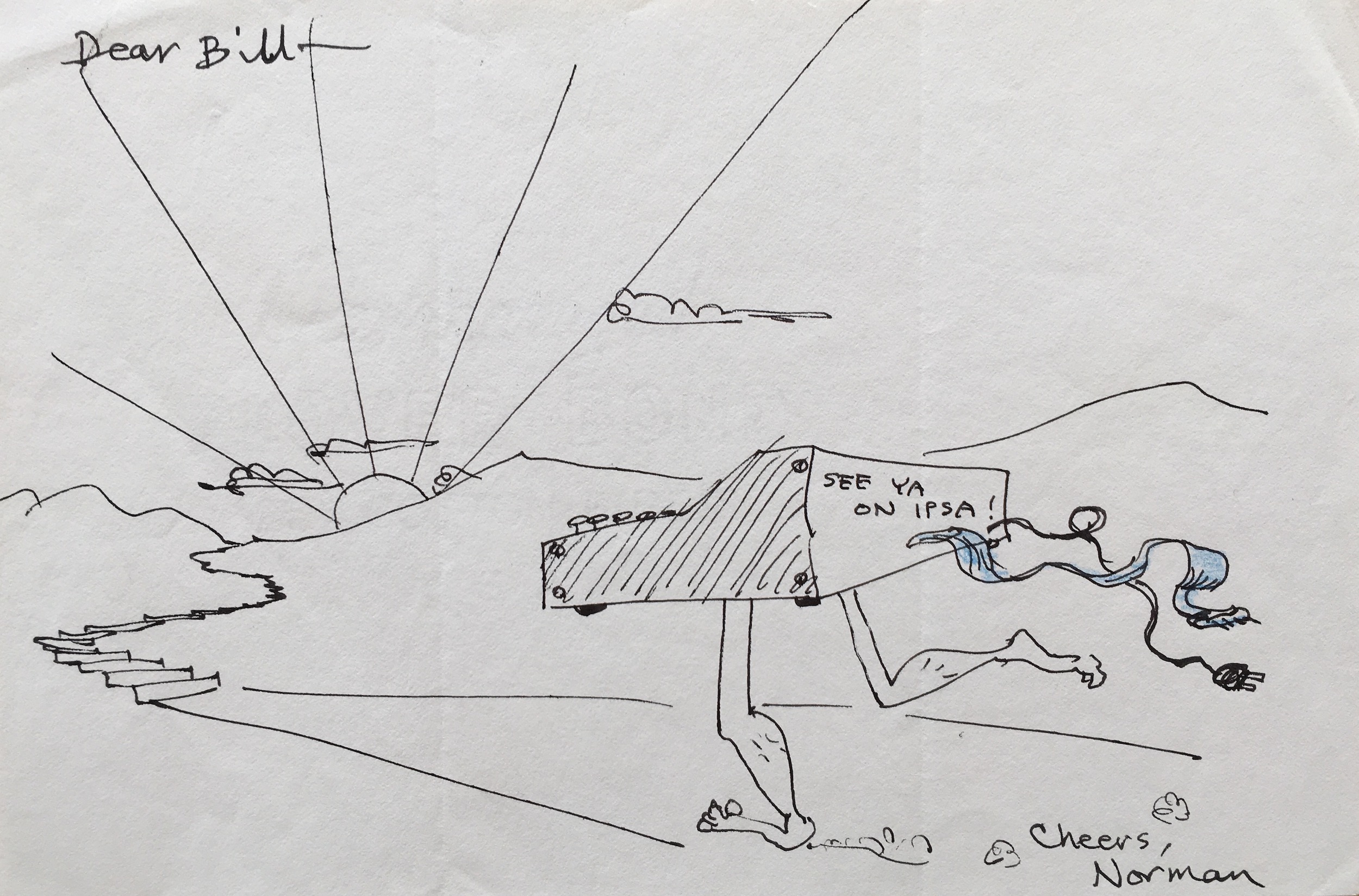

I started talking about IPSA with friends about the same time. There was an Art and Technology Conference in Toronto, and I met a guy named Bill Bartlett who lived in Pender Island, out in BC. Also another artist, Bob [Robert] Adrian, who lived in Vienna. They were mostly pushing Slow Scan TV. Bill Bartlett had already set up a network around the Pacific Rim, Hawaii, Australia, Japan, and other places where he could trade Slow Scan images. I said “Hey you guys ought to try out this IP Sharp system.” So they all got accounts and before long, we started trading messages back and forth. Most of it was pretty trivial stuff: “What’s the weather like, there? How’s the family?” That kind of thing. But in the back of our minds, we were trying to figure out what we could do to make this into art. Again, this is a very brittle medium, in which there are no images, just letters, numbers, and punctuation. Various people came up with different ideas. In 1985, Roy Ascott, who worked out of Wales, came up with an idea called ‘La Plissure du Texte’ whereby writing a storybook text was shared by characters assigned to each city. For instance, Pittsburgh was the Prince; and Toronto, the Fairy Godmother, and so on. You’d log into the I.P. Sharp system, and see what the other characters were up to. It was totally impromptu, you didn’t know where the story would lead. This went on for two weeks, totally paid for by I.P. Sharp.

That same year, in Toronto, Laura Kikauka, Carl Hamfelt, and I came up with another idea called ‘Hearsay’. We sent a message around the world using eight nodes of the I.P. Sharp network, whereby each node was translated into a different language along the way. Nobody along the chain knew what the original message was. The languages used were Spanish, English, Japanese, German, Welsh, and Hungarian, as it went around the world in 24 hours, finally arriving back in Toronto.

So these were some of the experiments that we did using IP Sharp, the recurring theme being the element of surprise: You take brittle material and try to turn that into something surprising and huma

The poem by Robert Zend was therefore translated into five languages (Spanish, Japanese, German, Welsh, and Hungarian) as well as into English several times during its journey across the computer network. Can you tell me a bit more about this process?

Yes. Zend’s widow hit a Return key that sent the original text to Des Moines, Iowa, where it was translated into Spanish. And you might ask: “Why Spanish in Des Moines, Iowa?” It just so happened that the person who ran the keyboard [Cindy Hilden] could speak Spanish. And then it went from Des Moines all the way to Australia. Now, why we couldn’t get anybody in San Francisco interested I don’t know, but they weren’t interested. So it went all the way to Sydney, Australia. And there, the coordinator [Eric Gidney] was slow in picking up the message, and I was constantly harassing him, like “you’ve got to answer, you got to do this!” Eventually, he did arrange to have it translated from Spanish back to English. And then from there, it went to Tokyo, Japan where it was translated into Japanese. From Japan it went to Vienna, and there Robert Adrian biked to the Japanese consulate, picked up the message, translated it into German, and sent it on to Wales. In Wales it went from German to Welsh. And then on to Pittsburgh, where it went back to English. Then from Pittsburgh to Chicago where it went to Hungarian (which was appropriate because Zend was Hungarian) and eventually back to Toronto. It is interesting to see the variations of the text, how it changed with certain elements somehow disappearing and then mysteriously reappearing again. I don’t understand how those reappearances (a sentence or two) occurred. The text was all based on Marshall McLuhan’s ideas of the message and the medium, so it was kind of a takeoff on McLuhan. In the documentation, you can read the whole sequence yourself. It’s quite entertaining to see how it changed.

From the perspective of our current interaction with computer networks, one might think of a fairly quick and automated process, but it actually involved people running around their city to find someone who would be able to translate the text, bring it back, type it on the computer, and send it. I can imagine it was quite stressing.

Yeah, it was weird. We were on pins and needles the whole time. But it was fun. We had a big map on the wall showing the progress of the message as it went around the world. We also used BBS (bulletin board systems) whereby people could send text messages over the telephone to various bulletin boards and share information. But it was pre Internet, although DARPA [2] was putting together the rudiments of the internet at about the same time.

Notes

[1] APL was invented by Dr. Kenneth E. Iverson, a farmboy from Alberta who was interested in teaching mathematics, and found traditional math notation to be inconsistent and ad hoc, so he invented something much better, which was neither: APL. Iverson and Bernecky worked together for a decade or more, and Ken won the ACM’s Turing Award for his work on “A Tool of Thought”. The Turing Award is computing’s equivalent to the Nobel Prize. Ian Sharp, recently deceased, was a founder of IPSA, and was the person who made IPSA a high-tech company long before the phrase “high-tech” even existed. Whitney Smith conducted an interview with Ian in March 1984, available here: https://www.ipsharp.org/[2] IPSAnet was a packet-switched network, just like ARPANET would be, designed primarily by Michael Harbinson and Roger D. Moore. The I.P. Sharp Newsletter archive (currently at www.snakeisland.com, but being moved to ipsharp.org) contains network maps and international office locations. The email traffic generated by Hearsay was carried by IPSA’s secure email system, “666 box”, first written before 1971 (which is when Bernecky started working at IPSA.)