Harold Cohen was a pioneer of computer-generated and Artificial Intelligence art. A successful artist, he started working with computers in 1968, upon his residency as a visiting professor in the Art Department at the University of California, San Diego. He created AARON, an autonomous program capable of creating artistic compositions with no external inputs. Cohen worked on the development of this program until the end of his life.

Website of Harold Cohen:

www.aaronshome.com

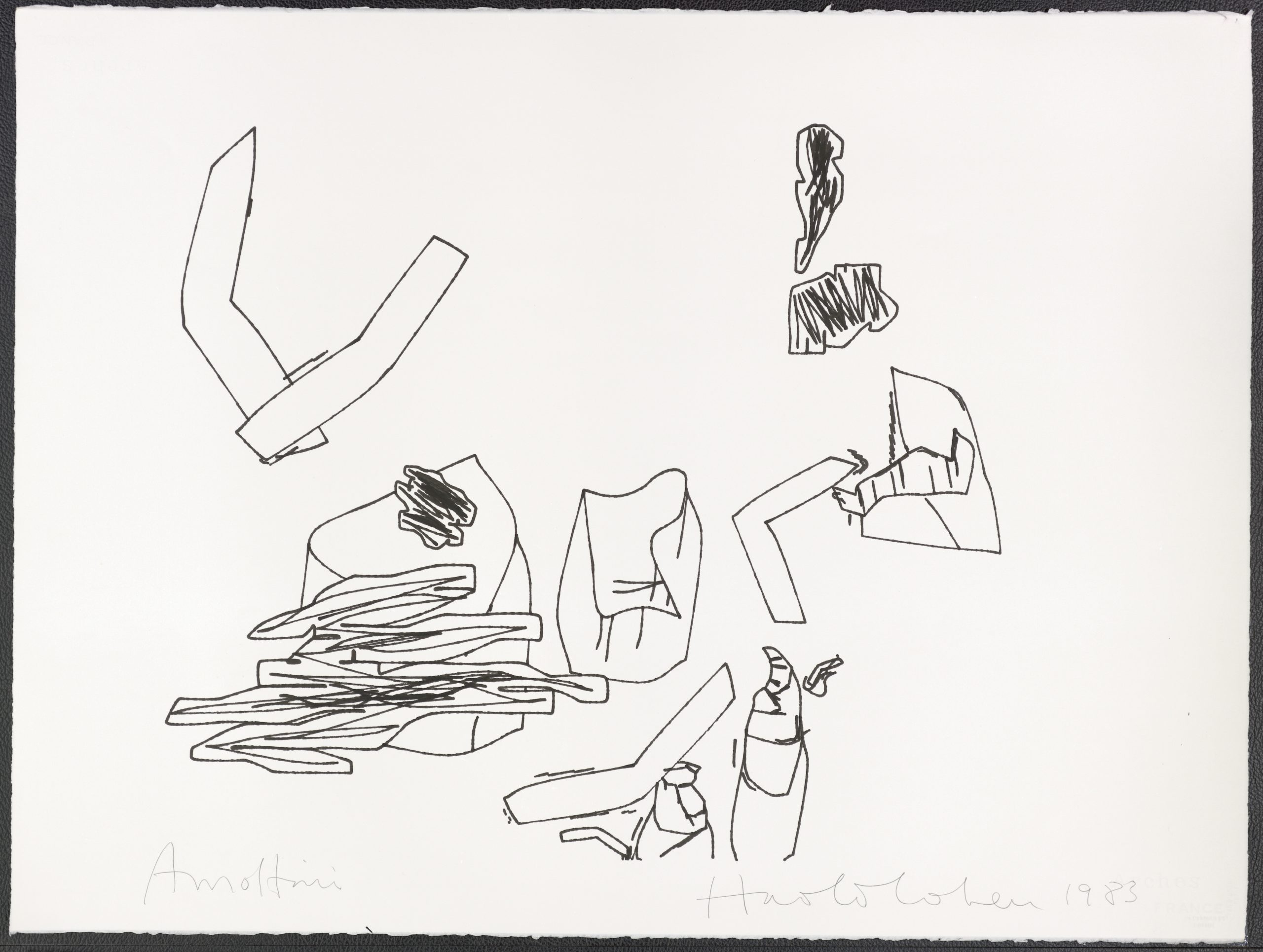

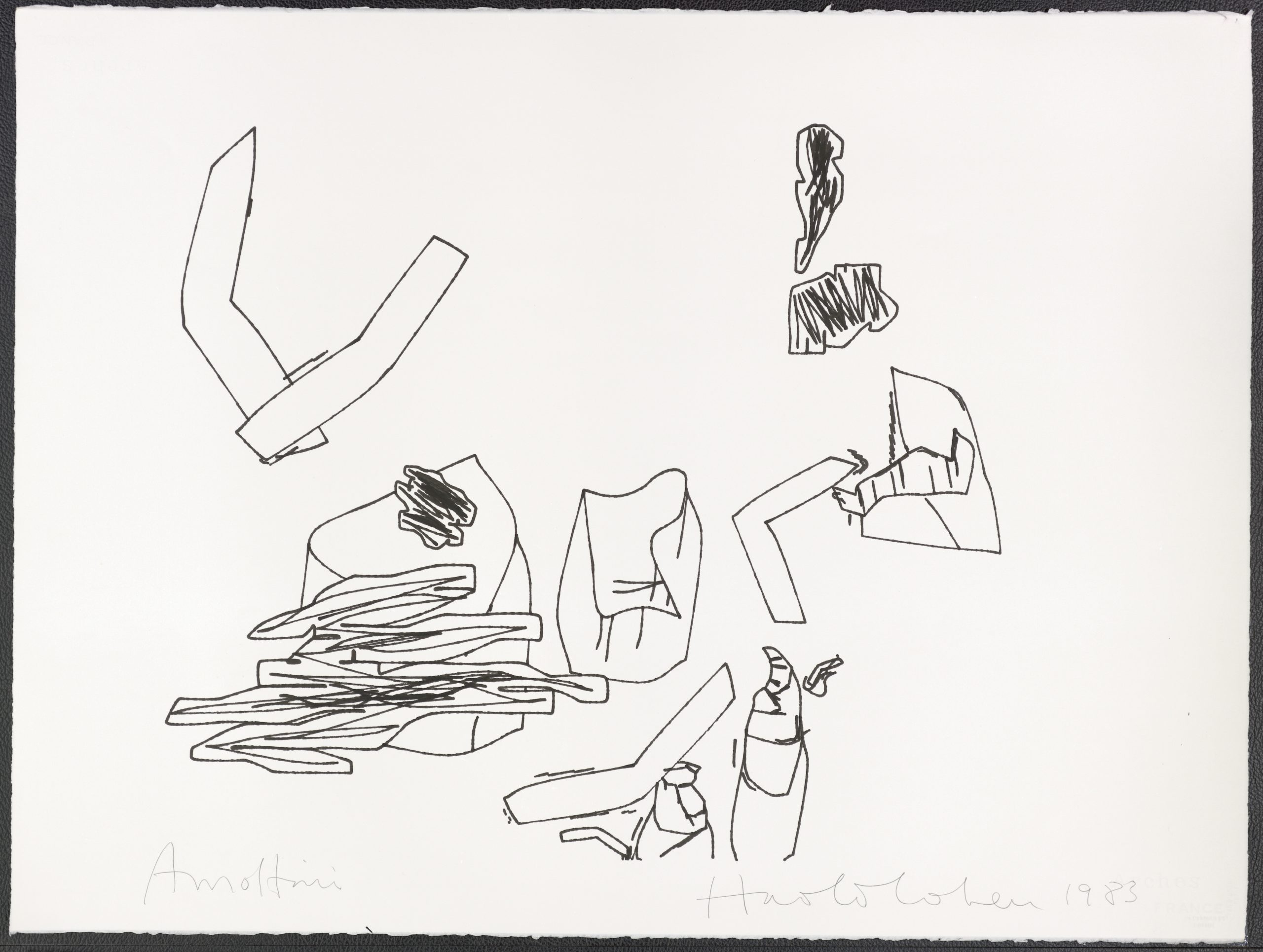

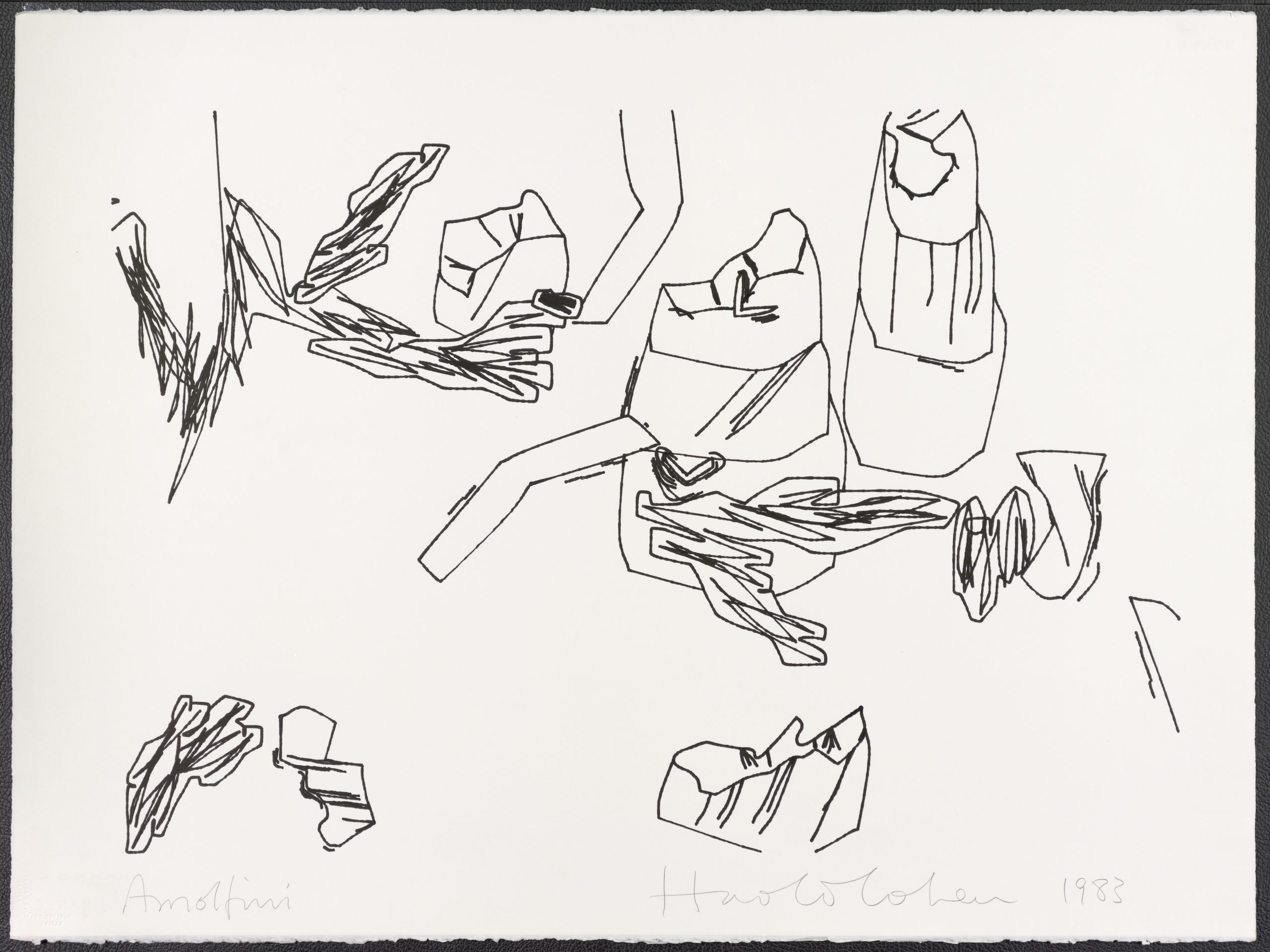

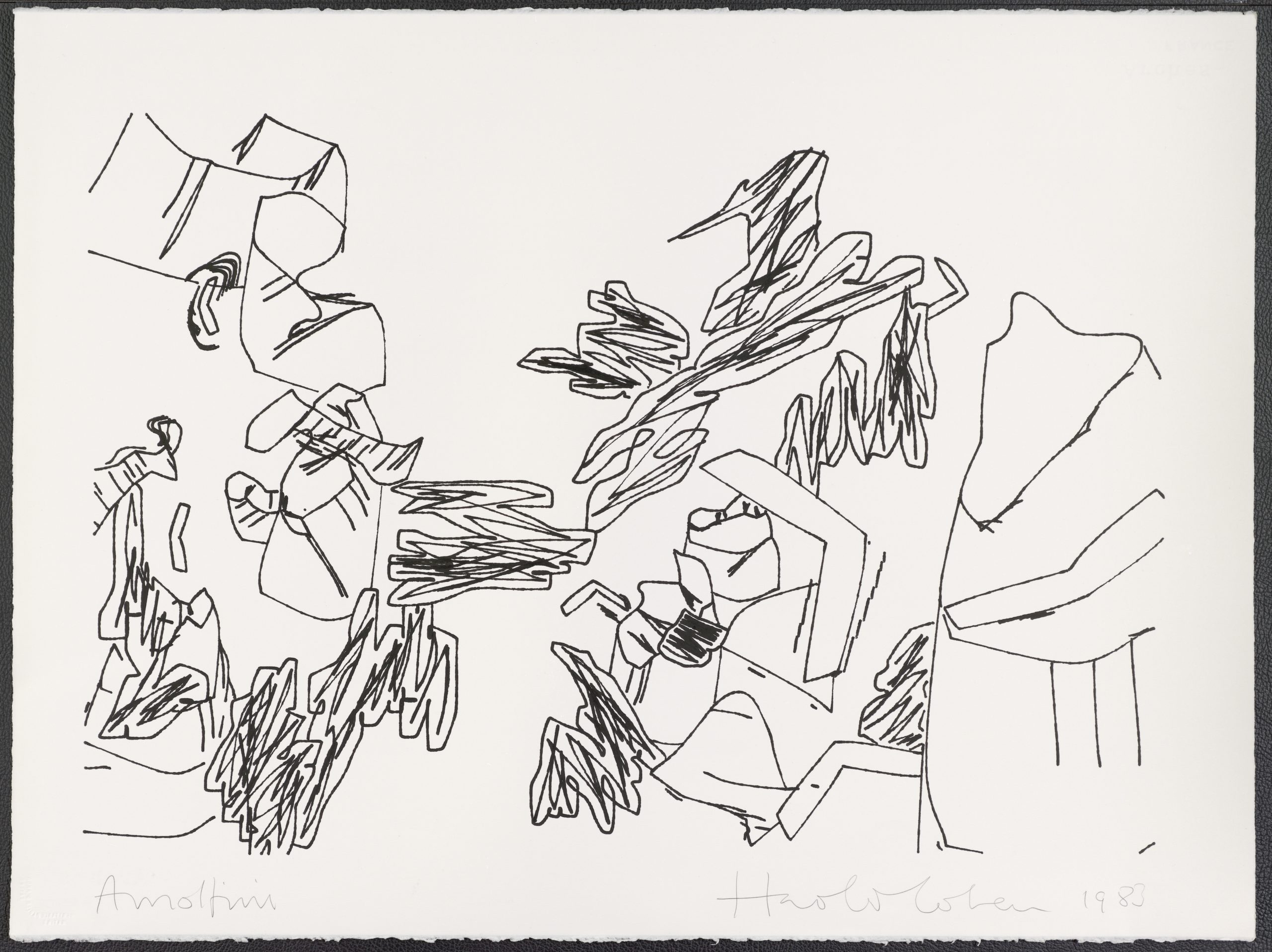

Arnolfini Series

Plotter drawings on paper created by AARON and exhibited at the Arnolfini Gallery in Bristol, 1983.

Making Art for a Changing World

Harold Cohen

Invited talk, RCAST, Tokyo University, 2002 (excerpt)

My own work […] is aimed at […] the vision of a computer program capable of functioning autonomously in relation to the making of art.

That vision has floated frustratingly beyond my reach for several years now – as, indeed, it has floated beyond the reach of Western culture from Pygmalion to R.U R. – and part of what I want to talk about is, simply, the idea of autonomy; what it is that AARON does and what stands in the way of it doing more. The other part of what I want to talk about, as a small scale model of the interacting forces that shape the futures we can’t predict, is the interaction of some of the various real-world forces that have made AARON what it is.

Art is shaped, not just by the technological imperative, but on how that imperative interacts with two other factors. First: what makes the work of an artist unique is the personal and idiosyncratic vision the individual brings to bear. And second: what makes the work of many artists within a culture alike – for we do have movements in art, not simply a collection of unrelated individuals — is the fact that art is fundamentally a cultural enterprise and that it is shaped also by its relationship to the culture it serves and that supports it.

As a preamble to AARON’s current work and to the question of autonomy, then, here’s a brief overview of AARON in terms of the interaction between these three factors factors – the technological, the personal and the cultural.

AARON began shortly after I met my first computer and was taken with the strange notion that, if a program could simulate an appropriate part of the human cognitive system, it might generate something very like human-made imagery. I’m still examining the consequences thirty-three years later. But after the first decade of development I concluded that the human cognitive system was what it was because it developed in the real world; and that an artificial intelligence that had a cognitive system but no external world to apply it to was fundamentally limited. AARON could not discover the external world for itself, but I reasoned that, just as children don’t have to go to Australia to learn about kangaroos, AARON could be supplied with some knowledge about the external world. I chose the part we know best and that has always provided the subject matter for art; namely, our own bodies; how they are put together and how they move.

[…]

I used to define autonomy by saying that the program should be able to make paintings in August that it couldn’t have made when I stopped working on it in January, implying that the key was purposeful self-modification. I find myself questioning now whether that was an appropriate definition or whether I wasn’t constructing exactly the same kind of human-referenced wall that kept AARON away from color for so long.

The fact is that I could not have anticipated the images AARON is producing now – images I could not have made myself — when I started work on trees four weeks ago. I could not have predicted when I finally broke through my brick wall that AARON would become in many ways a better, a more vigorous colorist that I have ever been. I could not have predicted any part of this history when I wrote my first trivial little program thirty years ago. That doesn’t satisfy my definition of program autonomy for the program, certainly, but it does something quite like it for the Harold Cohen/AARON entity.

As regards its place in the future, AARON has now laid claim to two very different positions. On the one hand, in its web-based manifestation, it became the first art-making program in history to provide original art on demand to anyone who wants some. On the other hand, two of its large prints have been hanging since the summer in the San Diego Art Museum; the first time in history that the work of a computer program, untouched by human hand other than the framer’s, could hang in the same context, and on the same terms, as art made by established human artists.

London (United Kingdom), 1928 – Encinitas, CA (USA), 2016

A radar engineer in the Royal Air Force, Harold Cohen studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Arts in London from 1948 to 1952. Later on, he developed a successful career as an artist during the 1960s, representing Great Britain at major art events such as the Paris Biennale (1961), documenta 3 (1964), and the 33rd Venice Biennale (1966). He also exhibited his work in many galleries and museums across Europe. In 1968, he moved to California for a one-year residency as visiting professor in the Art Department at the University of California, San Diego. This experience profoundly changed his career, as Cohen learned to program a computer using the FORTRAN programming language and began exploring new ways to create art. In 1971, he built his first drawing machine, which he displayed in an exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in 1972. He also built other devices, such as flatbed plotters, a robotic “turtle” that drew on enormous sheets of paper, and a painting robot.

However, the most outstanding art-making machine he created was the computer program AARON, which he wrote in 1973 and continued developing until his death in 2016. Cohen intended to understand which elements constitute an image and how a visual composition is built by delegating the process to a machine. AARON was therefore designed to “model some aspects of human art-making behavior, and to produce as a result “freehand” drawings of a highly evocative kind.” The program could generate an endless series of drawings that resembled human creations with no visual data or any external intervention. Cohen elaborated a complete series of rules, based on an observation of “primitive” forms of representation (from the petroglyphs of Native Americans to children’s drawings), and his own artistic production. These rules were structured in hierarchical levels, so that the program could, for instance, operate on the overall structure of the drawing (ARTWORK), assign a placement for each element (MAPPING), or elaborate each individual shape (PLANNING). The structure considered even the basic line or stroke, which could result from a series of twenty or thirty instructions on three different levels of the system.

In the initial creation and development of this program, from 1973 to 1975, Cohen was influenced by the ideas around Artificial Intelligence (AI) that were being discussed at Stanford University’s Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, where he was a visiting scholar, and in fact AARON is considered a pioneering example of AI art. The artist frequently completed the drawings, adding colour by hand, and later on increased the complexity of the shapes and compositions that AARON could generate, which included recognisable images of people and plants. In the 1990s, he replaced the drawing machines by painting machines, and then in 2002 he started used wide-format printers. In the last years of his life, Cohen could no longer paint on a canvas, so he devised a system that allowed him to add colour to AARON’s drawings using a touch screen.

Harold Cohen has exhibited his painting machines in numerous exhibitions, among which the documenta 6 (1977) in Kassel, where he demonstrated the Turtle, and several one-person exhibitions at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (1977-78), the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1979), the Tate Gallery (1983) and the Computer Museum in Boston (1995), among others. His work was also featured in the group exhibition Digital Pioneers at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (2009-2010), and can be found in the public collections of Tate Gallery, London; Victoria and Albert Museum, London; The Arts Council of Great Britain; The Gulbenkian Foundation; The Contemporary Art Society, London; The Los Angeles County Museum; The Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; The Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; The Brooklyn Museum; and the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, among others. Since 2009, AARON can be seen at work in a permanent installation at the Carnegie Science Center in Pittsburg.

Cohen, H.(1974). On Purpose: An enquiry into the possible roles of the computer in art. Studio International, Vol 187, No 962, January 1974, pages 11-16. [EN]

–– (1979). What is an Image?. AARON’s Home. [EN]

–– (1982). How to make a Drawing. AARON’s Home. [EN]

–– (1988). How to Draw Three People in a Botanical Garden. AARON’s Home. [EN]

–– (1994). The Further Exploits of Aaron, Painter. AARON’s Home. [EN]

–– (1999). Colouring without Seeing: A Problem in Machine Creativity. AARON’s Home. [EN]

–– (2004). A Sorcerer’s Apprentice. AARON’s Home. [EN]

–– (2006). AARON, Colorist: from Expert System to Expert. AARON’s Home. [EN]

–– (2016). Fingerpainting for the 21st Century. AARON’s Home. [EN]

Menezes, C. (2017). Delving into coding: the art of Harold Cohen. Studio International, August 10th, 2017. [EN]

Nake, F. (2019). Georg Nees & Harold Cohen: Re:tracing the origins of digital media. In: O. Grau, J. Hoth & E. Wandl-Vogt (eds.) Digital Art through the Looking Glass. New strategies for archiving, collecting and preserving in digital humanities. Donau: Donau-Universität, p.30. [EN]

–– (2019). Harold Cohen. Einzigartig. Exhibition catalogue. Berlin: DAM Gallery. [DE]

Strimpler, O. (1995). The Robotic Artist: Aaron in Living Color. Harold Cohen at The Computer Museum. Boston: The Computer Museum. [EN]

Publications

1965

Robertson, Bryan: Harold Cohen. Catalogue Introduction for Whitechapel Gallery Retrospective of Harold Cohen.

1966

Thompson, David: Harold Cohen. Catalogue Introduction for Venice Biennale, David Thompson.

1967

Bowness, Alan: Contemporary British Painting. Catalogue Introduction for Stuyvesant Foundation Exhibition.

1971

Van Deren Coke: The Painter and the Photograph. Univ. New Mexico Press. 1971.

1973

Burnham, Jack: Encylopaedia Britannica Yearbook on Science and the Future. Section on Art and Technology.

1978

Roth, Moira: Harold Cohen on Art and the Machine. Art in America.

Reichardt, Jasia: ROBOTS: Fact, Fiction and Prediction. Thames & Hudson/Viking/ Penguin Books, 1978.

1979

Forge, Andrew: On Harold Cohen’s Drawings. Catalogue Introduction for San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Roads, Curtis: An Interview With Harold Cohen. Computer Music Journal. Vol. 3, #4, issue 12. December 1979.

1983

Compton, Michael: Harold Cohen. Catalogue essay for Tate exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery. 1983.

Boden, Margaret: Creativity and Computers. Catalogue essay for Tate exhibition catalogue.

1984

Franke, Herbert W: Harold Cohen. Computergrafik-Galerie.

1985

McCorduck, Pamela: AARON, The Universal Machine. McGraw-Hill. 1985.

Franke, Herbert W: Computer Graphics – Computer Art. Springer-Verlag, 2nd Edition, 1985.

1986

Johnson, George: The Finer Arts, in: Machinery of the Mind. Times Books. 1986.

Dietrich, Frank: The Computer: A Tool for Thought-Experiments. FD-Thought Experiments, 1987.

1987

McCorduck, Pamela: Science and Meanings in Art, in: WHOLE EARTH REVIEW #55, 1987.

Goodman, Cynthia: Digital Visions – Computers and Art. Abrams, 1987.

1988

McCorduck, Pamela: Artificial Intelligence: An Apercu. DAEDELUS. Winter 1988.

Galloway, David: Die Muse in der Steckdose. Kunstforum – Asthetik des Immateriellen. 1988.

1989

McCorduck, Pamela: Artificial Intelligence: An Apercu, in: The Technological lmagination, 1989.

Ferrier, Jean-Louis: An Artwork That Creates Art, in: Art of our Century. Prentice Hall Editions, 1989.

1990

Boden, Margaret: The Creative Mind. Myths and Mechanisms. Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1990.

Kurzweil, Raymond: The Age of Intelligent Machines. MIT Press, 1990.

1991

McCorduck, Pamela: Can Computers Create?. Art & Antiques. April 1991.

McCorduck, Pamela: AARON’S CODE: Meta-Art, Artificial Intelligence and the Work of Harold Cohen. Freeman, 1991.

1993

Mellor, David: The Sixties Art Scene in London. Phaidon Press, 1993.

1994

Holtzman, Steven R.: Digital Mantras. MIT Press, 1994.

Nake, Frieder: Drei gleich Funf: Pioniere der Computerkunst, in: Computer Art Fascination.

Matthews, Robert: Computers at the Dawn of Creativity. New scientist.

1995

Associated Press: Computer Shows Skill as an Artist.

Holmstrom, David: Programmed Arm Rivals Artist’s Hand. Christian Science Monitor.

Saunders, Michael: The Rembrandt of Robots. Boston Globe.

Holtzman, Steve: Painting by Numbers. Technology Review.

La Recherche: Un Robot Peut-il Etre Un Artiste?

Matthews, Robert: Schopferische Schaltkreise. Focus Extra Magazine.

Highfield, Roger: AARON…Master Draughtsman. Daily Telegraph.

Cohen, Paul: The Virtues of Theories of Ill-defined Behavior, in: Empirical Methods for Artificial Intelligence. MIT Press, 1995.

1996

Boden, Margaret: Artificial Genius. Discover Magazine.

Weber, Jack: But Is It Art? PC Pro Magazine.

1997

Levy, Stephen. Man versus Machine. Newsweek Magazine.

Clancey, William: AARON the Artist (chapter and cover), in: Situated Cognition. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Johnson, George: The Artist’s Angst Is All in Your Head. New York Times.

Boden, Margaret: AARON the Artist is a Robot of Rare Proclivities. ComputerLink. San Diego Union Tribune, 1997.

1998

McCorduck, Pamela: AARON’S CODE: Meta-Art, Artificial Intelligence and the Work of Harold Cohen, Japanese Edition, 1998.

1999

IAMAS Annual: Machine Creation. Japan, 1999.

2000

Weber, Jack: Harold Cohen. PC PRO.

2001

Balint, Kathryn: Brush With Creativity. San Diego Union Tribune.

Dailey, Linda: AI Program Creates Museum Art. COMPUTER.

2002

Matthews, Robert: Ah, But is it Art?”. Daily Telegraph, London.

2004

The Sixties. Tate Gallery Calendar.

Schmiederer, Ernst: Kunstliche Kunst: Harold Cohen und AARON. INFINEON Magazine, Austria.

Takiguchi, Noriko: Self-Portraits of the Future. AXIS Magazine, Japan.

Pincus, Robert: He, Robot. San Diego Union Tribune.

2005

Tomas, David: Harold Cohen: Expanding the Field: the Artist as Artificial or Alien Intelligence. Parachute.

2007

Lugo, Matt: Comments and Observations on AARON. Catalog essay for AARON’s World (Lisbon) exhibition.