Interview: Frieder Nake Discusses Algorithmic Origins and True Computer Images with Bettina Munk

This interview was originally published on Lines Fiction, an online resource on contemporary drawing and animation curated and produced by Bettina Munk. Text courtesy of Bettina Munk.

Bettina Munk: Listening to your stories about the origins of computer graphics, I get the impression that the early days around 1960 were an inspired time of experimentation unconcerned with the division between the analog and the digital. Not yet categorized were the early images created by Herbert W. Franke, who was a physicist that ventured into the field of visual representation. Around that time you became a computer scientist and an artist. Is it right that computer science came after the first computer graphics?

Frieder Nake: The first answer is a plain “yes”: when the first graphic images emerged from the computer, computer science (“Informatik” in Germany) didn’t yet exist as a distinct academic discipline. But such a plain answer needs to be modified carefully by a supplementary explanation: In the beginnings of computer graphics, Informatik did not exist as an independent academic discipline. There was not yet a field of research and study, explicitly concentrating on computable processes. They were not an established university institution.

However, research on computers and computing took place within the scope of mathematics and electrical engineering, to some extent also in linguistics. There was numerical mathematics, using computers to approximate solutions to mathematical problems. And there was engineering work on hardware. Concrete work always comes before the establishment of a new discipline. The same was true with computer graphics.

The Computing Center in Stuttgart, as elsewhere too, assumed computer tasks for the whole university.

Bettina Munk: What we have to consider – around 1960 there were hardly any digital but analog computers outputting curves, no digits. Was this aspect a reason for physicists and computer scientists to develop artistic images?

Frieder Nake: No. But caution: this statement can only be made for me. I didn’t develop a single digital image for the only reason that images came from analog computers.

Kurd Alsleben in Hamburg through a friend got access to an analog computer at DESY [short for Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron, a national research centre for fundamental science], and the two together generated a series of simple drawings. Others may have done the same, too.

Bettina Munk: Your artistic credo, expressed in Max Bense’s “artificial art”, collided with the beliefs of artists and their audience that did not want to tolerate that a plotter would be the author of an art work. The first-ever exhibition of digital art took place in 1965 with drawings generated by programs and driven by punched tapes. That happened at the Studiengalerie in the Hahn building in Stuttgart. In “edition rot” the computer images are documented, and Max Bense added the manifesto for this: “Projects of generative aesthetics”.

Frieder Nake: I can only confirm that. Yes, the first exhibition of computer graphics with an aesthetic impetus was opened on February 5, 1965, in the Hahn building, Stuttgart, with drawings by Georg Nees. The building didn’t belong to the university. The university rented two levels of the building, the 7th and 8th floor to be used for philosophy and literary studies. Max Bense, Elisabeth Walther, Fritz Martini, Käthe Hamburger were working there.

For the opening, issue 19 of the booklet series rot was published by Hansjörg Mayer. Whether it documented exactly what could be seen in the exhibition, I don’t remember. I assume, there were a few more works in the show.

Later on, I called the superb, but hard to read text by Bense, the “Manifesto of Algorithmic Art”. In rot 19, this term is not mentioned. But I think, the text deserves to be included in the collection of Manifestos of Art.

I want to mention that Nees’ exhibition was not an official exhibition of the Studiengalerie. It is true, it took place in rooms of the gallery, and the Institute of Philosophy. And it was open to the public. But it happened without official blessings by the institutions.

Bettina Munk: The artworks came from programmed sources and, interestingly, weren’t created by professional artists but rather physicists and mathematicians. But feedback came from a curator at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. Jasia Reichardt curated an important and groundbreaking exhibition in 1968: “Cybernetic Serendipity”. Was Bense’s manifesto, the “Projects of Generative Aesthetics” from 1965, the big kick-off that acknowledged these computer graphics as art?

Frieder Nake: The “big kick-off”? Hui! I would be cautious … But Bense’s action had a great impact. Here is the story.

In 1965, Jasia Reichardt curated an exhibition of Concrete Poetry at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA). Max Bense was an advisor. After the end of the exhibition, the two went for a walk through London, maybe together with Siegfried Maser and Hansjörg Mayer. Jasia asks Bense: And what should I do next? Bense says: Computer Art!

This happened around half a year after Nees’ exhibition in Stuttgart. A daring move! For the ICA it was a completely different dimension. Big and international. It took three years until, in August of 1968, “Cybernetic Serendipity” opened with Jasia Reichardt as curator and Max Bense as advisor.

The German magazine, Der Spiegel, became aware of computer art, even long before, and they wrote a slightly smug article about Bense, Nees, and Nake. Two TV channels, Panorama and Aspekte, produced TV reports with me at the Computing Center of the university. So there was a reaction in Germany on the national level. I don’t know of similar reactions in any other country.

Bettina Munk: So the first to program and exhibit computer graphics in Germany were Georg Nees and Frieder Nake. Also in Croatia, in Zagreb, existed an important scene for programmed art in the late 1960s, and in 1970 the Venice Biennale presented a special show with computer-generated work as experimental art. But even when there was a long-term exhibition entitled “Impulse Computerkunst”, managed by the Goethe Institute, the idea of artificial art didn’t gain ground in the art world. Only in the 21st century, when everybody got his and her pocket computer and engaged with digital imagery on a daily basis, this art form became fully accepted.

Frieder Nake: A. Michael Noll made similar artwork in the USA that he also exhibited in 1965. His work is interesting and important. It has to be mentioned here.

The special exhibition in Venice, 1970, was focused on computer-generated art in a wider sense. Dietrich Mahlow from the Kunsthalle Nürnberg organized an exhibition of constructivist art in 1969, and then became curator of a special exhibition in the center fold of the Venice Biennale, entitled “Proposal for an Experimental Exhibition”. Russian Constructivism, Concrete Art, Op Art, and Algorithmic Art were presented.

Bettina Munk: For a while, you too took a break for from making art, and completely concentrated on computer science?

Frieder Nake: During my year 1968/69 in Toronto, where I successfully developed a comprehensive program entitled “Generative Art I”, I had second thoughts. My doubts didn’t leave me, until in Vancouver I wrote three short texts: “Statement” (page 8, 1970), “There should be no computer art” (page 18, 1971) and “Technocratic Dadaists” (page 21,1972). Thereafter, I withdrew from the art world until about 1984. During this time, I concentrated on computer science, and the scientific side of computer graphics as a mathematical discipline. And I was involved in politics on the side of the New Left.

Bettina Munk: Back to the pioneers in algorithmic art, were there no women?

Frieder Nake: In retrospect, from a distance of over fifty years, and pretty much without any doubt, we can say that the first three exhibitions were by Georg Nees in February 1965 (Stuttgart), by A. Michael Noll in April 1965 (New York), and Frieder Nake in November 1965 (Stuttgart).

Towards the end of the 1960s, first experiments with computers began by Vera Molnar and Manfred Mohr, and then Harold Cohen’s unique career with computer work began. Putting aside the rat race of “who … when”, without a doubt Vera Molnar is a pioneer of algorithmic art. A Hungarian from Paris, she is the great old lady of Computer Art. Until this day, with the age of 95, she creates new works.

In 1968, Lillian Schwartz was able to enter a kinetic sculpture into the landmark MoMA exhibition, “The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age”, curated by Pontus Hultén. In the same year, she started work at Bell Laboratories in Murray Hill, New Jersey, where she became a long-term Artist in Residence, and in this time created some of the earliest computer animations.

Joan Truckenbrod’s first works are known to be from 1975, when she started with a great series of pieces. For sure we can say that in the seventies quite a number of women knew how to create programmed computer art. Joan emphasizes the term “Algorithmic Art”.

Bettina Munk: You once wrote that the aesthetics of digital images cannot be grasped in a single piece, but in a visual schema. This aspect might be incompatible with a concept of art focussing on the work of art as a unique piece, rendering the replica worthless. The term Algorithmic Art fits better these days, as we’ve grown accustomed to digitally-generated images that can be true or fake.

In recent decades, you had a fundamental interest in questions concerning art and replication. You describe how artistic intuition and the concept of a drawing get influenced by the process of programming the computer. You describe that a doubling occurs.

Frieder Nake: The algorithmic image, fundamentally, exists in form of a double. What does this mean? As every other image, the algorithmic image is a sign in the first place. That means that the image in itself becomes a signifier, if we assume that it bears a message. In other words, we interpret the image in one way or another. By the process of interpretation, the image becomes a sign. This applies to every image. The algorithmic image, however, is interpreted twice: by the human and by the computer (or, to be more precise, by a software running on the computer).

Thus, two interpretants exist as result of the interpretation, as Charles S. Peirce put it in his semiotic theory. We have an intentional interpretant on the side of the human interpreter, and a determined interpretant on the side of the machinic interpreter (these words are my add-on to Peirce’s theory; “interpretant” is the result of a process of interpretation). The algorithmically-generated image becomes was I call an algorithmic sign.

The fascinating thing is: the determined interpretant on the side of the computer only formally exists as the result of an act of interpretation. For the computer is totally incapable of interpretation. Its act of “interpreting” shrinks to an act of determining. The computer software is always only determining the singular “meaning” a sign may represent for the computer. As a machine, it is supposed to perform exactly one action, and never anything else. People nowadays talk about this situation as “digitization”, which is quite off. But that is another area of discussion.

I describe the algorithmic sign as a semiotic entity possessing a surface and a subface. The surface is perceptible by our senses, it is for us; the subface is computable, it exists for the computer software.

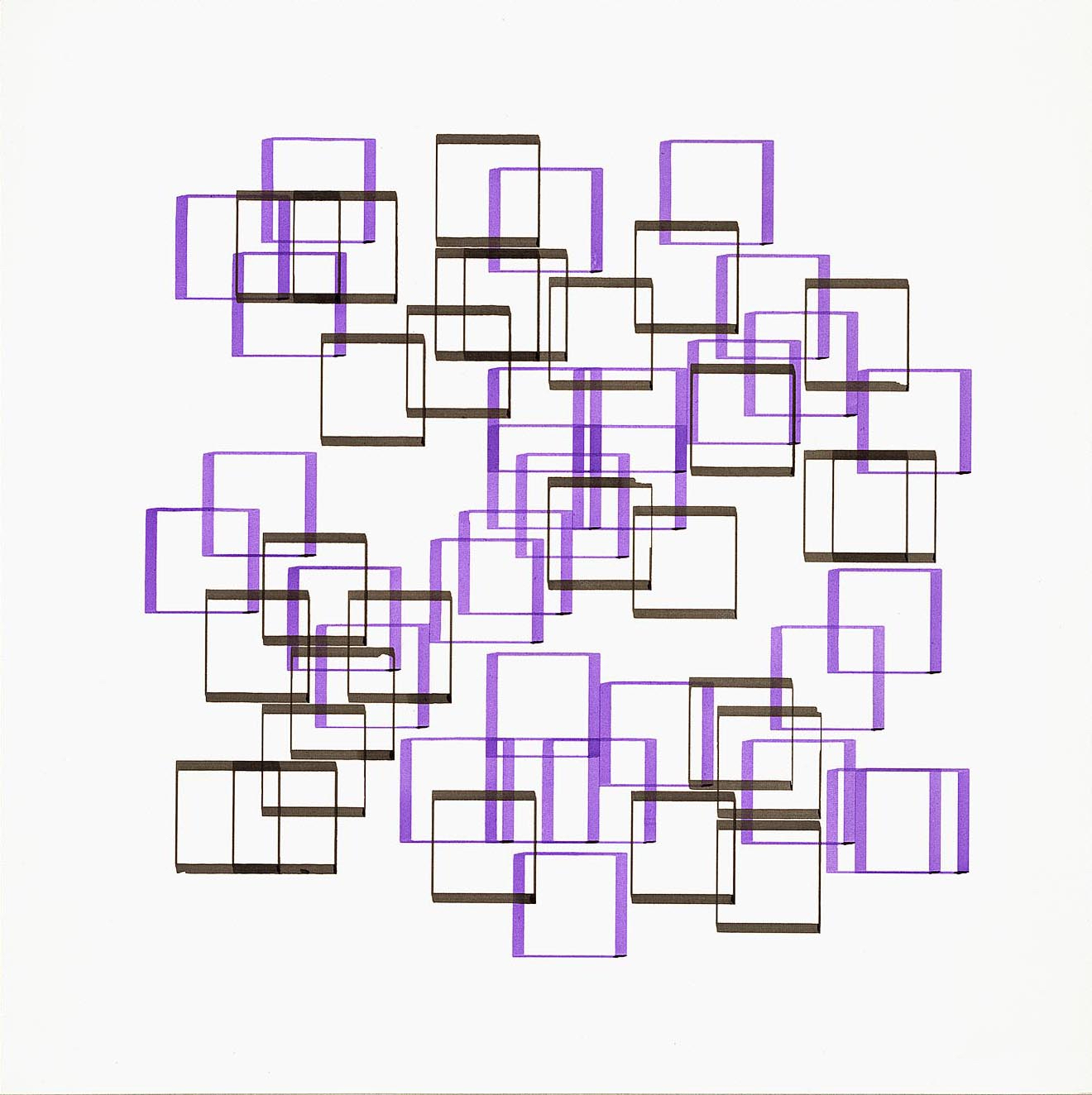

Generating images by computer, I also like to say: Think the image, don’t make it. Why? Because the process of the actual making is assigned to the computer. Therefore thinking can unfold the image’s full potential. It results in an algorithm. The algorithm confronts us with the entirety of possible images computed by it.

To think an image then means to think the infinity of all images that can be generated by the algorithm under consideration. The single image is only a representative or an instance of the class of images it belongs to. We can see the whole (the class) only in its part (the single image). The visible image is our comfort, given the unsettling wasteland that the infinite stream of possible images represents. But a static image will probably be even more obsolete in the near future — the public sphere will be dominated by streaming moving images. Their single representatives will be relegated to quiet places of withdrawal, in far-off corners of the world.

A nice side effect of the withdrawal: the art market would disappear. That wouldn’t be so bad.

With the emerging algorithmic image, a new kind of exhibition is possible, where the subfaces play a role. For we would soon want to see them. We would want to examine them, see them in action.

Bettina Munk: In your opinion the term Digital Art is too vague, you prefer the term Algorithmic Art — why? And what defines Algorithmic Art?

Frieder Nake: If people with their own ideas want to create images, and they decide to use the computer as their instrument, they need to program. They must write a program. If the program runs on a computer, and a drawing, an image emerges, the computer with the program is the processing medium. Computer and program together can only become a processing medium if the artist created the program. The program is the operational description of the work. The work of the artist. If he or she hasn’t made any mistakes, the description will generate a lot of similar, visible pieces of work. The program is the description of a whole class of work pieces! That was unheard of before. The crucial point in making art with a computer is the presence of a program with an abundance of parameters (variables): the operational description of an infinite number of images. That was a revolution.

Basically, programs are “algorithms”. If we call this art “digital”, we emphasize what’s unremarkable about it, namely the methods of encoding and saving.

Bettina Munk: If a pictorial scheme produces many similar results, it’s only natural to ask about making choices. Is it true that the selection of the first computer images were left to chance operations?

Frieder Nake: No, no! The selection was not given to chance operations. Heaven forbid! If it would be, the wish-wash of the computer as an artist would suddenly make sense. But this is nonsense, for “sense” is not a computable category. Let me put it this way:

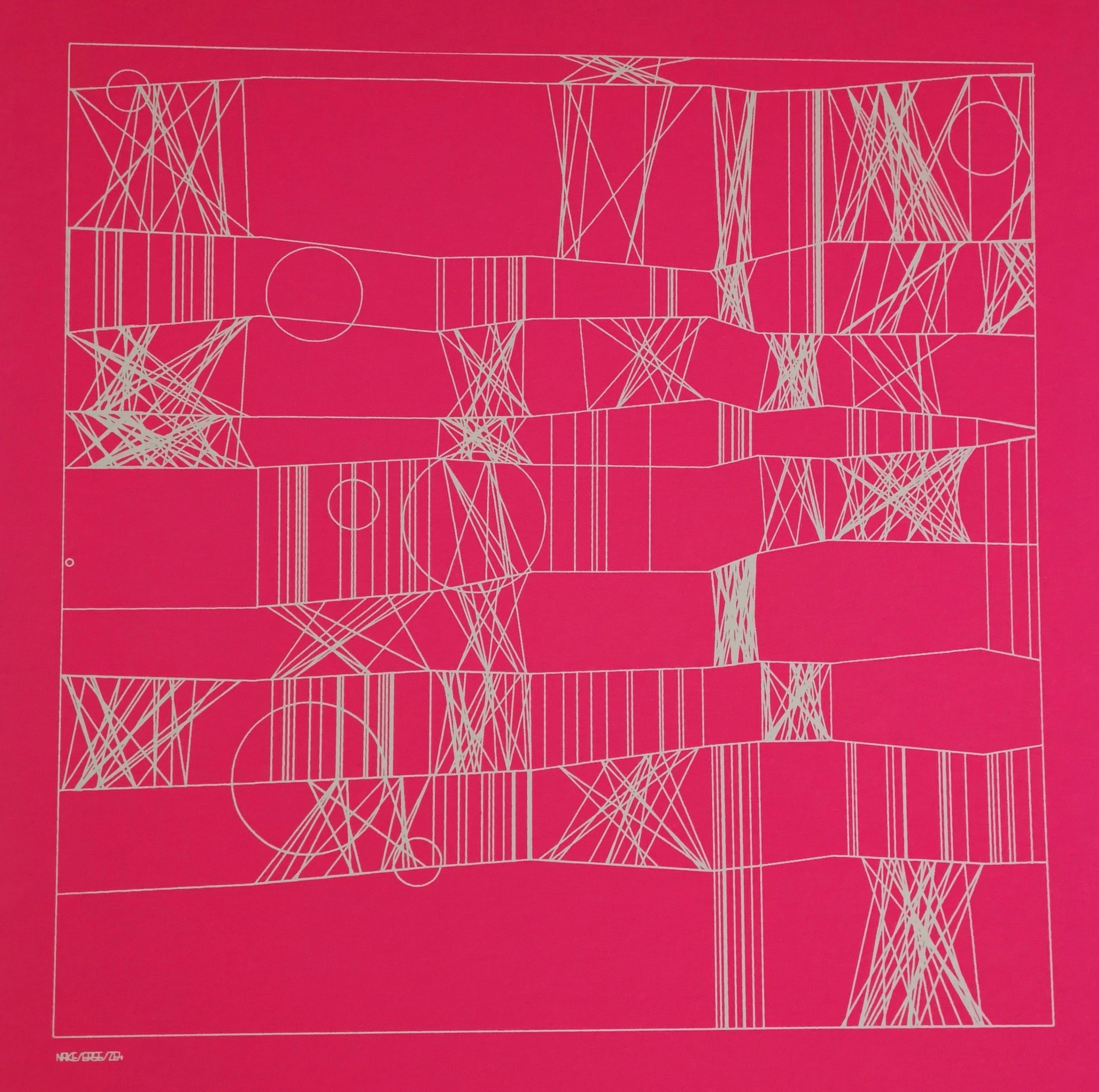

In generating, calculating, and computing an image by program, random number generators play a significant role. These are programs that appear as if producing chance results, but that is not the case. The results of their calculations show seemingly chaotic dynamics, which means, we have problems understanding and predicting them. Such pseudo-random processes on the computer stand for the intuition of the traditional creative artist. The results of the processes are only predictable within the boundaries of probabilities.

Okay. Let’s assume a program has output a small number of pieces, say five, or ten, or 39. Now it’s my job to decide which of these I want to discard and destroy. First, the pieces are only stored on the computer, I want to materialize them only after my selection is done. That’s, of course, a matter of taste only. I could try to do it in a rational way. But I act like any other artists in selecting their work. Well, I could act out this selection process. Which may be funny, once or twice.

Bettina Munk: Today, Informatik and algorithmic art are well established, and generative aesthetics are accepted. With artificial intelligence on the rise, computer-generated drawings are part of the canon. Yet, some digital art that works with chance operations still causes discomfort, and is dismissed as cold and arbitrary.

A digital program that pragmatically renders visual outputs is okay, but if the composition is left to chance, and no longer the product of creative intention, some people decline it. Did this happen to you?

Frieder Nake: People in the art world, who might even only be bystanders that never created any visual artwork, if they have second thoughts when it comes to working with chance operations — these people are not to be taken seriously. Not at all. Art history, at least in the 20th century, is full of serious experiments with randomness, and discussions about the role of coincidence in art. I tolerate these people, but I don’t talk with them. Period.

I consider this attitude ridiculous, and childish in its naivety. But let me add the following (so as not to appear too arrogant):

A computer leaves nothing to chance. Never ever. For the computer is the machine of computability. Period. (Here I don’t explain, what it is — computability, it is exactly defined in mathematics.) Everything on the computer is computed, even what we call “chance”. To talk about chance on the computer is pretty much nonsense! (But I do it also.) Instead, we should talk about “pseudo-chance”. That is a kind of chance pretending to be chance. I could go into more detail, but won’t do it here, in order for you not to get a lengthy answer. Just a footnote added:

When it comes to art in relation to computers, a lot of nonsense is uttered. In particular, people who don’t have a clue about technology, mathematics, computers, programs, and the strictly rational talk a lot of nonsense, because they think (and they are right) that everybody may interpret everything anew, at any time. That’s allowed, but it often ends up in nonsense.

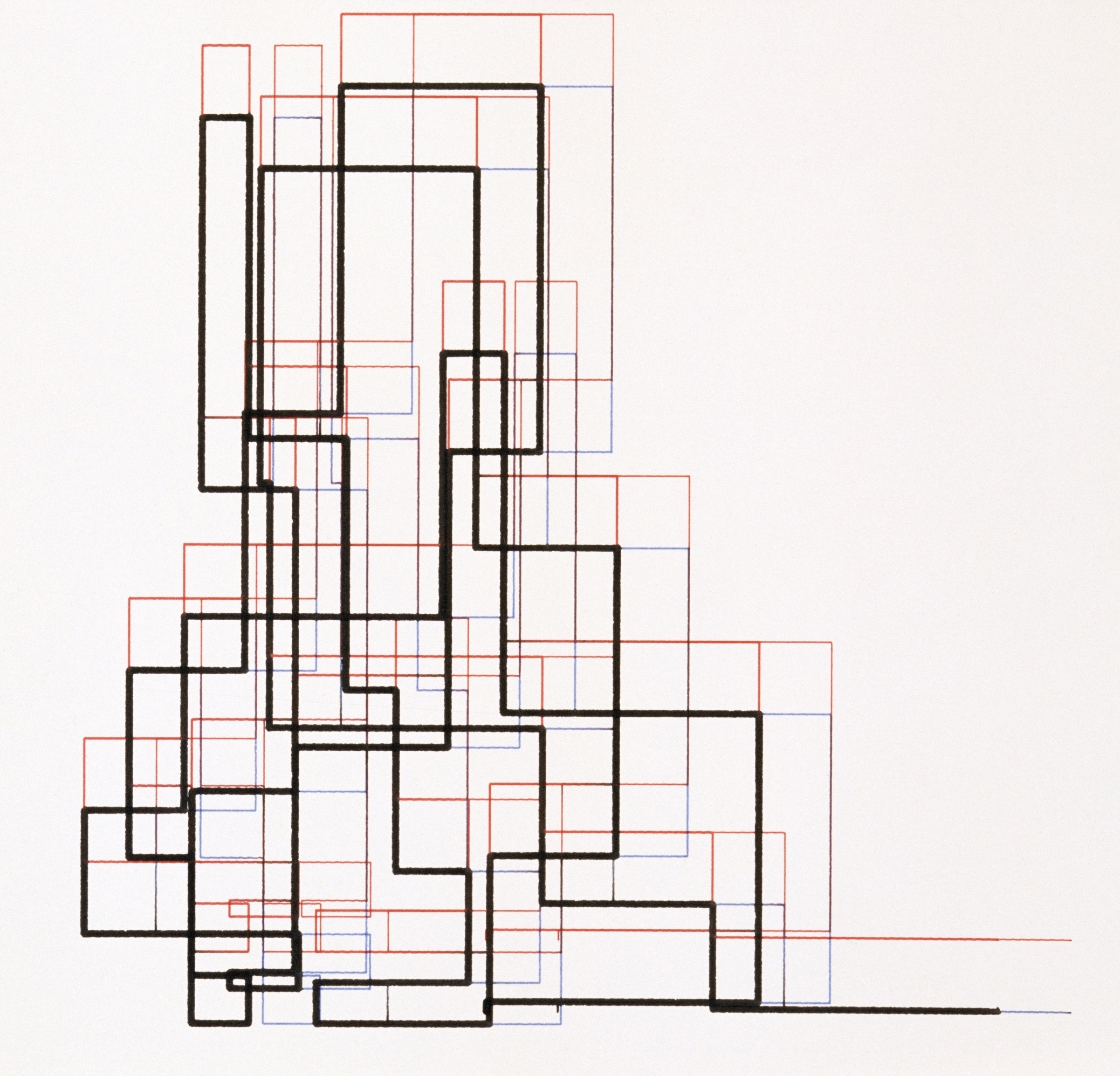

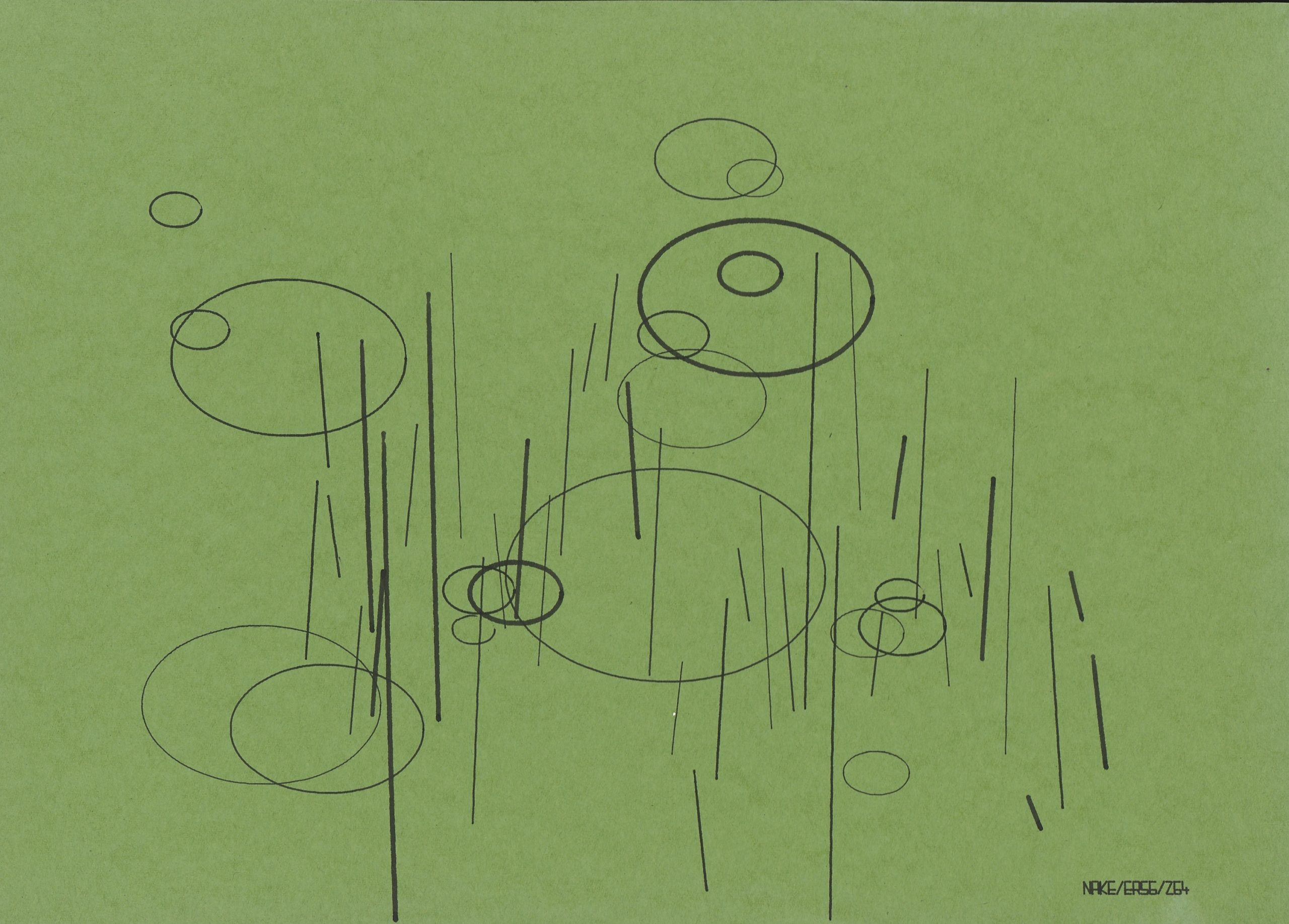

Bettina Munk: Your drawing series “Homage à Paul Klee” from 1965 was completed after a certain time — there are 100 prints, a silkscreen edition of 40, and of course the image “13/9/65 Nr. 2”. Was it a predetermined limit?

Frieder Nake: No, never. I write a program. I decide on its completion. I let it run, once or many times. I choose the images that I like, and of which I keep one copy.

People were fond of the image 13/9/65 Nr. 2, they wanted to have it. I let it redraw from the punched tape as a doubling of the original (for it wasn’t printed). The drawing process, in this case, took three hours. I sold the images rather cheap. Today it’s a bit more, around fifty-fold. I have gone through this procedure perhaps twenty or thirty times, before I decided to make a silkscreen edition of 40. They’re spread all over the world.

Today, I still make series from time to time, small ones, with 20 or 40 variations. They all are original drawings, no reproductions of one and the same. If I want to have 40, I generate 100 or 200 in a tearing pace, and then I choose. That takes a long time. After the selection I have a digital printing studio print the copies on paper.

Bettina Munk: If the computer processes a visual schema that is not focused on a single composition, it lends itself very well to the moving image. If the computer-generated image is manifold, it may result in an animation. When did moving images gain importance for you?

Frieder Nake In 2004, I had a solo show at Kunsthalle Bremen. I was proud of the invitation. I said, I’m pleased to accept, but only if I may present some interactive installations in the exhibition. Together with students, we created four installations. Additionally, we made one dynamic installation, that showed the results of a running program on four parallel screens, each displaying different images.

By now, I was convinced that the moving image is the genuine computer image, which means, the image generated at this very moment. Why did I consider this to be the truly novel aspect of the algorithmic image?

The reason is that the computer is a great performer for all locally determined procedures. More accurately, computers are machines that in absolute certainty perform simple calculations in large numbers, and in permanent iteration. Computers stand out by processing big quantities absolutely reliable. Humans are the direct opposite. When we focus on this quality of the computer’s performance, only then we can realise its true mediality. Mediality in the sense of the aforementioned infinite stream of moving images.

There are two types of moving image that profit from this: the interactive and the animated moving image. A film repeats a limited image sequence. But the dynamically calculated image is the actual computer image, for it never recurs. The interactive image in addition opens towards the user; there it has its strengths and weaknesses. Aesthetically, the interactive image is problematic (and by now, it somehow has lost much of its attraction).

The short answer to your question: in 2004 I began creating moving images.

Bettina Munk: With interactive works, the viewer contributes to the drawing process, and shapes the outcome. How do you consider these results in your art?

Frieder Nake As mentioned above, in my work the first dynamic installations emerged together with the interactive installations. They were presented at the Bremen exhibition in 2004. And afterwards, this exhibition opened at ZKM in Karlsruhe; one of the interactive installations was also shown in Ingolstadt, in the Museum for Concrete Art. The four installations that I developed together with a wonderful group of students gave me a lot of pleasure. The students were great. While being different in their interactive behaviors, the installations were following common patterns. For each installation, I chose a different drawing from my early works, from 1965 and 1969. We then discussed, how we could transform the old static images into interesting interactive forms. We decided that two people at once may manipulate the piece Hommage à Paul Klee. They could ‘catch’ elements of the image independent of each other, and change the elements’ positions. We interpreted the lines of the drawing as if they were of elastic material. If dragged to some other location, the whole drawing followed elastically, and every element found its new position, until the user let go. Then the image snapped back and swung until it rested in its original form.

I had much fun with these four experiments. However, I believe that the opportunities for interactive installations are rather limited. You must reflect on them very carefully, in order not to be corny or arbitrary.