There should be no Computer Art

Frieder Nake

Bulletin of the Computer Arts Society, October 1971, p. 18-19.

Soon after the advent of computers it became clear that there was a great potential application for them in the area of artistic creation. Before 1960, digital computers helped to produce poetic texts and music; analog computers (or only oscilloscopes) generated drawings of sets of mathematical curves and representations of oscillations (see e.g. [3], [5] and [7] ). But it was not before the first exhibitions of computer produced pictures were held (1965) that a greater public took notice of this threat, as some said, –progress, as others thought. The threat and progress being the use of an extremely complicated, sophisticated, expensive and rational machine in the arts, i.e. in one of the last refuges of the irrational, as some believe. And it took another three years before there was a tremendous breakthrough caused by two big international exhibitions of “computer art” (“Cybernetic Serendipity”, London 1968, “Computers and Visual Research”, Zagreb 1969).

Since then, a serious discussion has been going on in the art world about the consequences and implications of the use of computers. Art magazines are full of articles, exhibitions are held everywhere, seminars are offered by art schools, books are published, portfolios are sold. Computer conferences have their computer art sections, computer journals publish technical papers. Computer scientists are flattered by the Iittle public success they make and amused by the interest artists develop. Artists surrender to the pressures of the new technique or laugh at the results, and get humiliated by the attitudes that scientists assume when they try to communicate with each other.

The discussion centers around the question “is it or is it not art?”, and is heated, often extremely ignorant and prejudiced, showing virtually no progress, highly repetitive, although the few interesting new methods and the little knowledge of computers that one needs have been published several years ago. (See e.g. [4]. For a recent survey including a bibliography, see [8]).

I was involved in this development from its beginning onward (1964). I found the way the art scene reacted to the new creations interesting, pleasing and stupid. I stated in 1970 [6] that I was no longer going to take part in exhibitions.

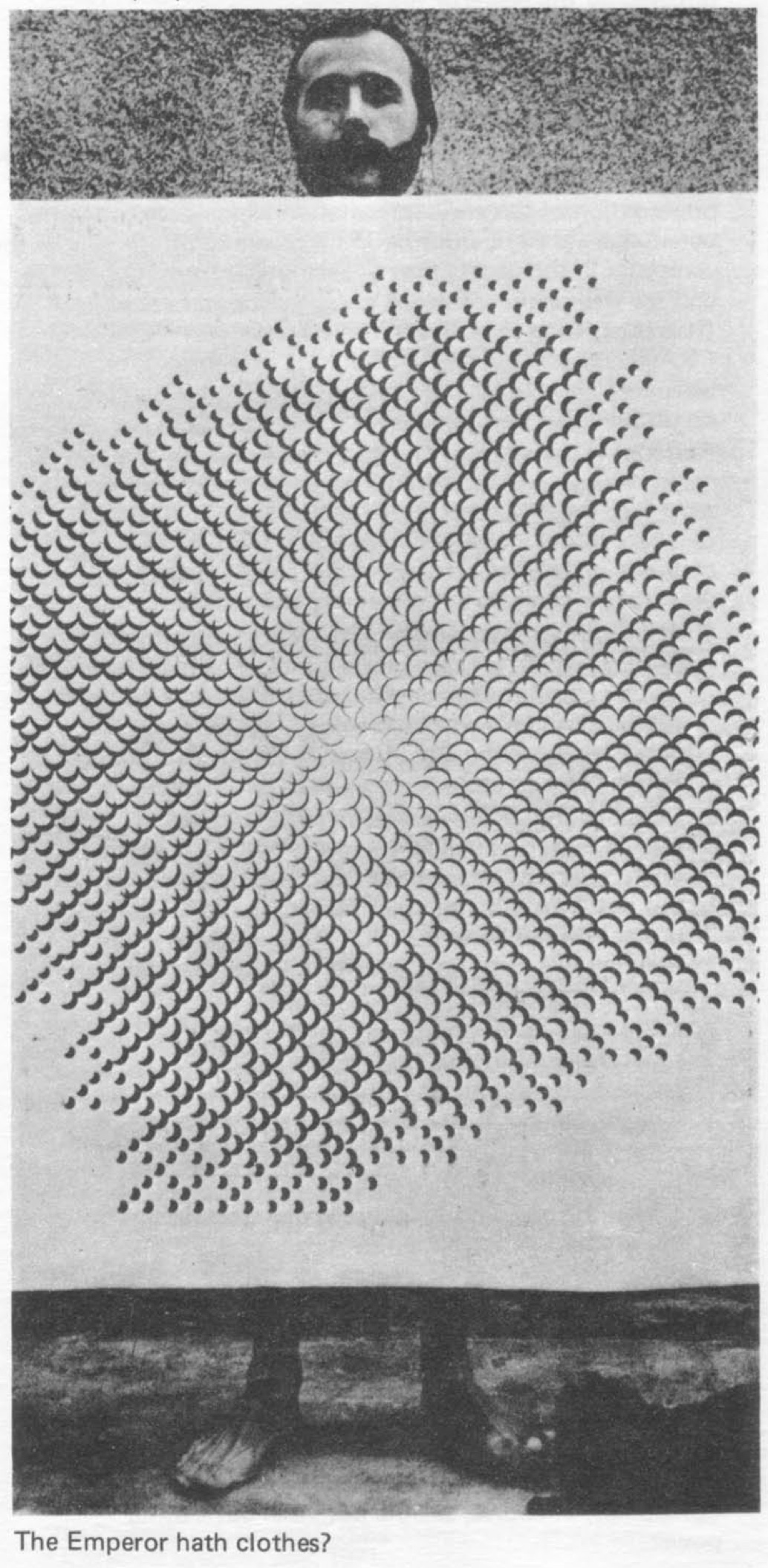

I find it easy to admit that computer art did not contribute to the advancement of art if we judge “advancement” by comparing the computer products to all existing works of art. In other words, the repertoire of results of aesthetic behaviour has not been changed by the use of computers. (This point of view, namely that of art history, is shared and held against “computer art” by many art critics, compare e.g. [2] .)

There is no doubt in my mind, on the other hand, that interesting new methods have been found, which can be of some significance for the creative artist. And beyond methodology, but certainly influenced by it, we find that a thorough understanding of “computer art” includes an entirely new relationship between the creator(s) and the creation: BENSE uses the term “art as a model for art” in this context [1].

The dominating and most important person in the art world today is the art dealer. He determines what is to be sold and what is not. lt is the art dealer who actually created a new style, not the artist. Progress in the world of pictures today is the same as that in the world of fashionable clothes and cars: each fall, the public is presented with a new fashion, artificially (sic!) created almost a year before in the centers (Paris, London for clothes, Detroit for cars, New York for pictures).

Differences from one year to the next are rarely ever substantial, in the majority of cases they are superficial and geared according to the salesmen’s requests and analysis of the market.

lt seems to me that “computer art” is nothing but one of the latest of these fashions, emerging from some accident, blossoming for a while, subject matter for shallow “philosophical” reasoning based on prejudice and misunderstanding as well as euphoric over-estimation, vanishing into nowhere giving room to the next fashion. The big machinery, still surrounded by mystic clouds, is used to frighten artists and to convince the public that its products are good and beautiful. Quite frankly, I find this use of the computer ridiculous.

ln many publications on “computer art” we read complaints that “real” artists do not have access to computers because of the forbidding expense of the machine, and because of the artists’ lack of knowledge in programming. We also read that we could obtain really interesting and new results if artists had the opportunity (money) to realize their ideas using a computer, perhaps being helped by programmers and mathematicians.*

At the same time, artists become aware of the role they play in providing an aesthetic justification of and for bourgeois society. Some reject the system of prizes and awards, disrupt big international exhibitions, organize themselves in cooperatives in order to be independent of the galleries, contribute to the building of an environment that people can Iive in.

I find it very strange that, in this situation, outsiders from technology should begin to move into the world of art and try to save it with new methods of creation, old results, and by surrendering to the given “laws of the market” in a naive and ignorant manner. The fact that they use new methods makes them blind to notice that they actually perpetuate a situation which has become unbearable for many artists.

Computers ought not to be used for the creation of another art fashion.

Questions like “is a computer creative” or “is a computer an artist” or the Iike should not be considered serious questions, period. ln the light of the problems we are facing at the end of the 20th century, those are irrelevant questions.

Computers can and should be used in art in order to draw attention to new circumstances and connections and to forget “art”.

There is no need for the production of more works of art, particularly no need for “computer art”. Art (better: the aesthetic object) comes afterwards (but it does come). Aesthetic information as such is interesting only for the rich and the ruling. For the others (and they are in the majority) it comes “with”. Namely with other information. Thus, the interest in computers and art should be the investigation of aesthetic information as part of the investigation of communication. This investigation should be directed by the needs of the people.

We should not be interested in producing some more nice and beautifuI objects by computers. We shouId be interested in producing a film on, say, the distribution of wealth. Such a film is interesting because of its content; the interest in the content is enhanced by an aesthetically satisfying presentation. That is, the role of the computer in the production and presentation of semantic information which is accompanied by enough aesthetic information is meaningful; the role of the computer in the production of aesthetic information per se and for the making of profit is dangerous and senseless. (lt is interesting to notice in this context that HELMAR FRANK, after a successful beginning in information aesthetics, gave it up and concentrated more and more on problems of education and psychology.)

Reiterating the argument: I don’t see a task for the computer as a source of pictures for the galleries. I do see a task for the computer as a convenient and important tool in the investigation of visual (and other) aesthetic phenomena as part of our daily experience.

As concrete projects to be investigated I propose:

1. The study of the alienation of the artist from his product which is caused by technology in general and by computers in particular (the distance between the artist and his work increases [1] ). What are the good, what are the bad effects of the division of labor taking place in art?

2. Investigation of the repertoires of signs used by individual artists and styles in the past and present. Such repertoires have been described occasionally, but not rigorously enough. The emphasis of such a project should be to describe those repertoires (and their various levels) in a way suitable for an application of information aesthetics.

3. Design and performance of experiments to test the significance of aesthetic measures defined so far; perhaps new definition of such measures.

4. Investigation of the importance of aesthetic information in various areas (education, propaganda, environments of work and living). This work would have to be based on a rigorous numerical definition of “aesthetic information”.

* ln some places, this is being tried by universities and companies; e.g. University of Madrid, Mathematisch Centrum (Amsterdam), Ohio State University, University of Toronto, IBM (the Whitneys) and others. Companies, of course, see the potential advertising power.

References

[1] M. BENSE: Cartesianische Aufklarung uber Kunst. Mitteilungen des Instituts fur moderne Kunst Nurnberg. Nr. 2/3. Mai 1971.

[2] J. BENTHALL: Technology and Art 15, Computer Graphics at Brunel. Studio International June 1970, 247-248.

[3] H.W.F RAN KE: Computergraphik-Computerkunst. Bruckmann Verlag Munchen. 1971

[4] M. KRAMPEN, P. SEITZ (eds.): Design and Planning 2. Hastings House, New York. 1967.

(5) F. NAKE: Erzeugung aesthetischer Objekte mit Rechenanlagen. ln: R. GUNZENHAUSER (Hrsg.), Nicht-numerische Informationsverarbeitung. Springer-Verlag Wien. 1968.

[6] F. NAKE: Statement, PAGE 8 1970.

[7] G. PFEIFFER: Kunst 10(1970). Kunst and Computer. Magazin 1883-1901.

[8] S.Y. SEDELOW: The Computer in the Humanities and Fine Arts. Computing Surveys 2(1970), 89-11 O.