Why Love Generative Art?

Jason Bailey

Over the last 50 years, our world has turned digital at breakneck speed. No art form has captured this transitional time period – our time period – better than generative art. Generative art takes full advantage of everything that computing has to offer, producing elegant and compelling artworks that extend the same principles and goals artists have pursued from the inception of modern art.

Geometry, abstraction, and chance are important themes not just for generative art, but for all art of 20th Century. As an art historian and an amateur generative artist, I see a clear line of influence on generative art starting from Cézanne and shooting straight through to the:

- Fracturing of geometry in Analytical Cubism

- Emphasis on technology, machine aesthetic, and mechanized production from Futurism, Constructivism, and the Bauhaus

- Introduction of autonomy and chance in Dada, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism

- Anti-figurative aesthetic, bold geometry, and intense color of Neoplasticism, Suprematism, Hard-edged Abstraction, and OpArt

- Use of algorithms by Sol Lewitt and others

To my eyes, all of these influences and more are tied directly into early generative art through to its modern-day practitioners. So I cringe when I hear the majority of my art-loving friends dismiss generative art as being irrelevant, not of interest to them, or even unworthy of being called art.

Every generation claims art is dead, questioning why it has no Michelangelos, no Picassos, only to have their grandchildren point out generations later that the geniuses were among us the whole time. We have a unique opportunity to embrace some of the most important artists of our generation while most of them are still living (and working). I hope to do my part in facilitating this through this article. Here we will explore why people so often struggle with generative art and:

- Offer a simplified definition of generative art

- Abolish ideas that credit machines for making generative art and not the artists themselves

- Give some non-technical examples of how generative art works

Hopefully, by the end of this article, you will either share my love for generative art or you will at least be able to intelligently communicate your distaste for the genre.

What is Generative Art?

One overly simple but useful definition is that generative art is art programmed using a computer that intentionally introduces randomness as part of its creation process. This often brings up two common but misguided viewpoints that hold people back from appreciating the beauty and nuance of generative art.

Myth One: The artist has complete control and the code is always executed exactly as written. Therefore, generative art lacks the elements of chance, accident, discovery, and spontaneity that often makes art great, if not at least human, and approachable.

Myth Two: The artist has zero control and the autonomous machine is randomly generating the designs. The computer is making the art and the human deserves no credit, as it is not really art.

The truth is that generative artists skillfully control both the magnitude and the locations of randomness introduced into the artwork.

Controlled randomness may sound contradictory, but if you are an artist or an art historian, you know that artists have always sought ways to introduce randomness into their work to stimulate their creativity. Thinking about the process of coding generative art as being similar to painting or sketching is actually spot on. In fact, we will see that the tool favored by most generative artists refers to the individual artworks produced as “sketches.”

Let’s Look at Some Early Examples of Generative Art

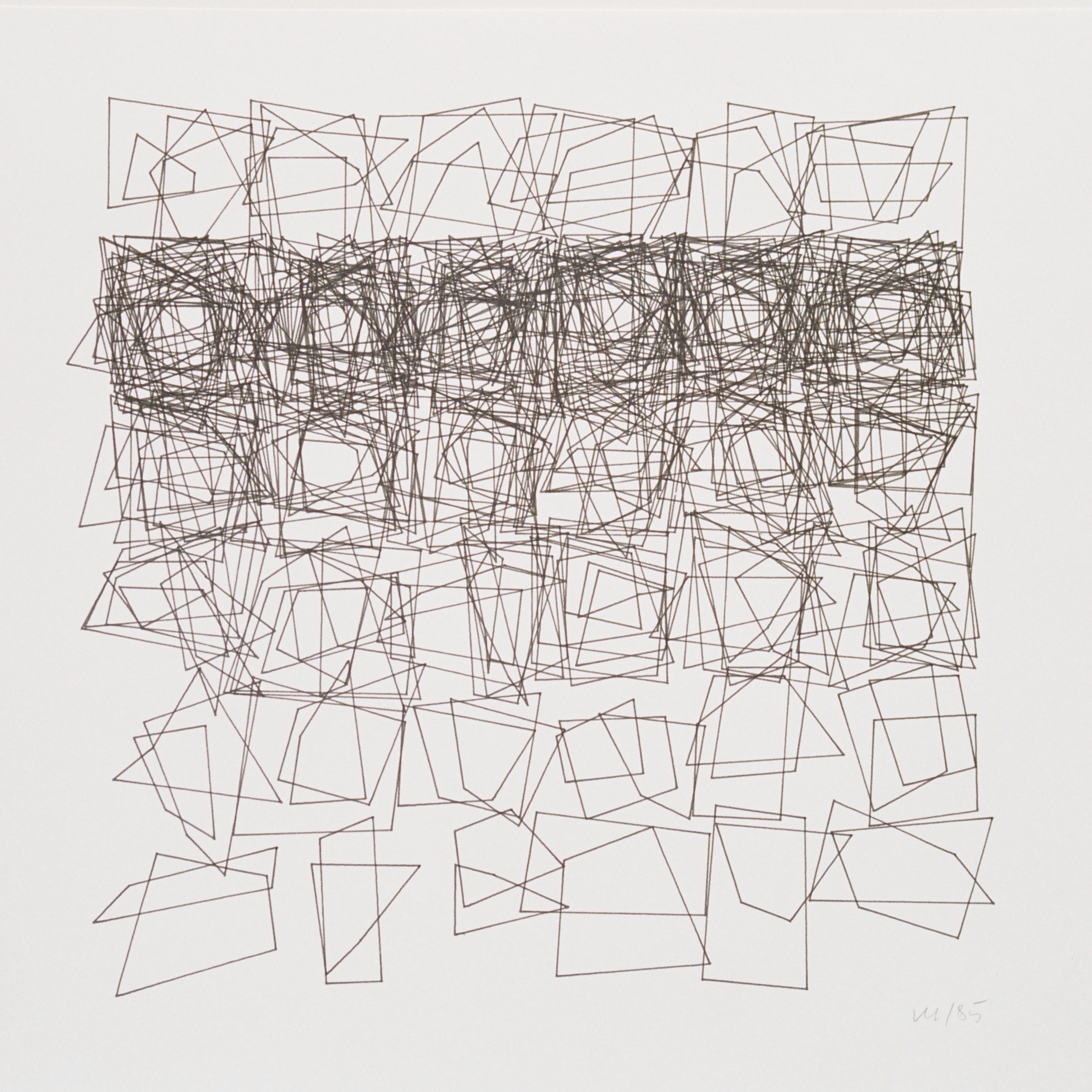

Let’s look at Georg Nees’ 1968 work Schotter (Gravel), one of the earliest and best-known pieces of generative art. Schotter starts with a standard row of 12 squares and gradually increases the magnitude of randomness in the rotation and location of the squares as you move down the rows.

Imagine for a second that you drew the image above yourself using a pen and a piece of paper and it took you one hour to produce. It would then take you ten hours if you wanted to add ten times the number of squares, right? A very cool and important characteristic of generative art is that Georg Nees could have added thousands of more boxes, and it would only require a few small changes to the code.

Unlike analog art, where complexity and scale require exponentially more effort and time, computers excel at repeating processes near endlessly without exhaustion. As we will see, the ease with which computers can generate complex images contributes greatly to the aesthetic of generative art.

As with many innovations, there were several pioneers exploring the potential for generative art in its first few years. Frieder Nake and Michael Noll, along with Georg Nees, were all exploring the use of computers to generate art. Back then, computers typically had no monitors, and the work was shared by printing the art on plotters, large printers designed for vector graphics.

Pioneering Women of Generative Art

It was hard for anyone to be a generative artist in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Computers were primitive, filled entire rooms, and access to them was extremely limited. Today most people grew up with computers in their homes and now carry them in their pockets. The majority of people in those early decades of computing had little to no contact with computers or frame of reference outside of science fiction. Against this backdrop and in a time where women faced tremendous sexism in the workplace, a large number of female generative artists emerged, making key contributions to the craft and the community.

Vera Molnár is one of the more prolific generative artists (a personal favorite of mine), and her work spans several decades. Below we see Molnár’s works from the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s.

Aware of the general perception of computers as cold, logical machines, Molnár spoke of the creative and humanistic gains it presented to her as an artist:

“Without the aid of a computer, it would not be possible to materialize quite so faithfully an image that previously existed only in the artist’s mind. This may sound paradoxical, but the machine, which is thought to be cold and inhuman, can help to realize what is most subjective, unattainable, and profound in a human being.”

To learn more about the important role women played in early generative art and to better understand how the genre has evolved into modern-day practice, including the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning, read the rest of Jason Bailey’s article “Why Love Generative Art?” in its original format on Artnome.com.