Oliver Laric questions the concepts of authenticity and uniqueness of the work of art by creating multiple versions of existing sculptures, remixing audiovisual content and even versioning his own work. An influential artist of his generation, his work is both conceptually and aesthetically representative of post-internet art.

Website of Oliver Laric:

oliverlaric.com

Reclining Pan (2019)

In this sculpture the satyr Pan reclines on a rocky base amid grape clusters and vines. His left hand clutches a goatskin called a nebris that he wears around his neck. Francesco da Sangallo carved this sculpture from a recycled piece of ancient marble and it once served as a fountain; its water spout is still visible at the mouth of the sack above his right arm.

Hundemenschen (2018)

Hundemenschen (2018) consists of sculptures cast in striated layers of pigmented resin. Referencing the long history of anthropomorphic sculpture, Laric contributes his own addition to the genre by melding resources from prehistoric to contemporary. The sculptures were initially 3D printed to create an initial cast for the final artwork. Hundemenschen are beguiling figures with a second layer of symbolism seen just below their polished surfaces—salamanders, crabs and human ears are suspended inside of them.

Sleeping Boy (2016)

The Sleeping Shepherd Boy was the first life-size figure modelled by John Gibson in Rome under the supervision of Canova. The subject, a classical shepherd boy, was prevalent among sculptors in Rome at the time – Canova’s Sleeping Endymion was modelled 1818, and Thorvaldsen’s Shepherd Boy in 1817. The Venetian master had accepted Gibson into his academy upon his arrival in the Eternal City at the relatively advanced age of 27.

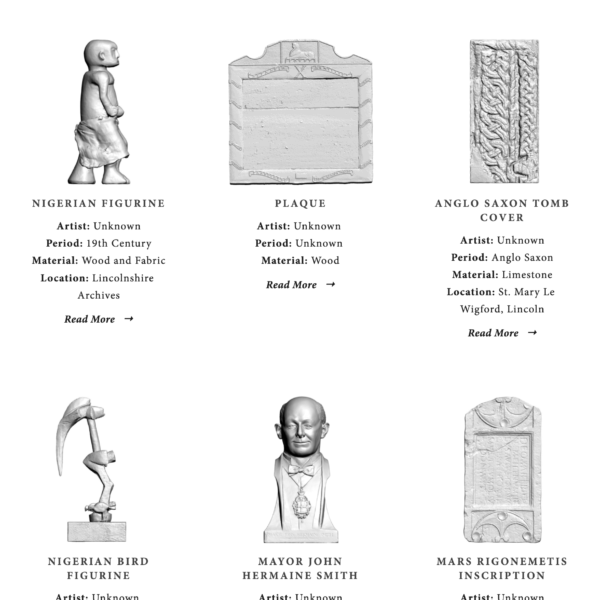

Three D Scans (2015)

A collection of 3D scans initiated by the artist in 2012, based on pieces from the collections of the following institutions: Albertina, Vienna; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; Theater Museum, Vienna; Musée Guimet, Paris; Musée des Monuments français, Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine, Paris; Dépôt des sculptures de la Ville de Paris; Musée Carnavalet, Paris; The Collection, Lincoln; Usher Gallery, Lincoln; Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze; KODE Artmuseums, Bergen. All scans can be downloaded and used without copyright restrictions.

Lincoln 3D Scans (2013)

The project started in 2012, when Ashley Gallant from the Collection invited the artist Oliver Laric to propose an idea for the Contemporary Art Society’s Annual Award for museums. Laric’s proposal to 3D scan and subsequently publish all data for free was chosen as the winning project. All 3D models on this website are scans of objects from the Usher Gallery and The Collection in Lincoln.

Kopienkritik (2011)

“Kopienkritik is a term popularized by German scholars, implying a view of Roman sculpture as a stand-in for something else, a mere reconstruction of lost Greek works. This marginalization of Roman innovation ignores qualities inherent in the works such as allusion, parody and emulation, also often falsely ascribing Roman sculptures to non-existent Greek precursors.”

Versions (2010)

Versions (2010) is the second of three official versions of this essay, and forms part of a larger project that includes “a series of sculptures, airbrushed images of missiles, a talk, a PDF, a song, a novel, a recipe, a play, a dance routine, a feature film and merchandise.” All of these components come together to create a meta-exploration of the topics raised therein: the relationship between copy and original, authorship, piracy, and reuse. Ultimately, Versions is a celebration of visual culture as a collective, social project, historically and in the internet-enabled present.

Relief (Utrecht) (2010)

“Some historic images make sense, as they echo current concerns and feel urgent and contemporary. The relief from Utrecht stands out… it’s probably the most impressive leftover from Reformation iconoclasm. It is in perfect destroyed condition; the damage is so well preserved. It has become an attraction because of its modification. That exemplifies the contradiction emblematic of iconoclasm; destroying an image always creates an image.”

Icon (Utrecht) (2009)

In collaboration with 3D modellers, Laric has translated a reformation damaged icon from St Martin’s Cathedral, Utrecht, into a silicone mould from which a number of casts have been made. Each is identical in size and form, distinction coming only from their varied pigmentation. For Laric, these sculptures, their multiplicity, reflects a viable productive principle in iconoclasm (Paul Pieroni).

Touch My Body (Green Screen Version) (2008)

The artwork comprises a modified music video by Mariah Carey in which everything other than the singer’s body is masked in a Chroma Key green screen, allowing others to create new versions of the video. Accessing the artwork on the artist’s website automatically downloads the video, inviting the viewer to create their own version.

50 50 (2007-2008)

A compilation of YouTube clips in which fans of hip hop musician 50 cent perform three of his songs. Accessing the artwork on the artist’s website automatically downloads the video, inviting the viewer to create their own version.

787 Cliparts (2006)

A fast-paced animation depicting human figures performing different actions arranged as a choreography. Accessing the artwork on the artist’s website automatically downloads the video, inviting the viewer to create their own version.

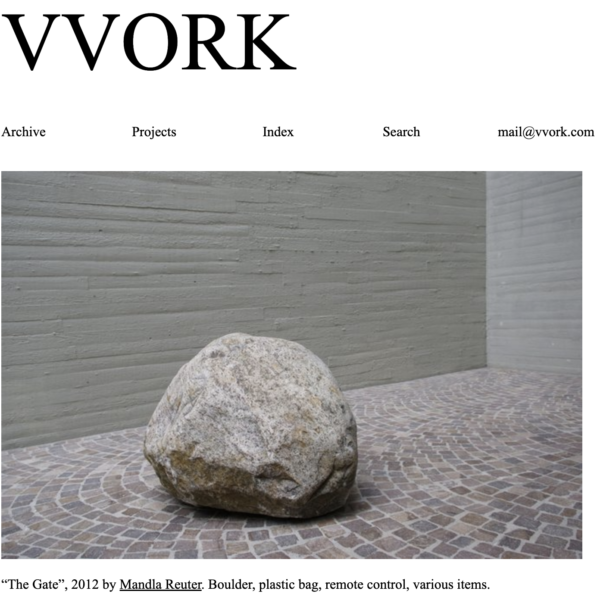

VVORK (2006-2012)

Created by Oliver Laric, Aleksandra Domanović, Christoph Priglinger and Georg Schnitzer, VVORK was an influential contemporary art blog. Active until 2012, the site regularly featured visual documentation of artworks and exhibitions that reflected the group’s vision of the contemporary art world, and also suggested the idea of establishing connections between artworks rather than considering the work of an artist the isolated output of a single creator. The site is currently archived at the Rhizome Artbase.

Versions

Oliver Laric, 2009

Voice over from video

An image published by the media arm of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard in 2008 shows four missiles. The above illustration suggests that the second missile from the right is the sum of two other missiles in the image, the contours of the billowing smoke near the ground and in the immediate wake of the missile match perfectly. Three days after the initial doctored image was published, an alternate version was released showing only three missiles. This exposed enhancement was followed by a public continuation of image manipulation. Anonymous authors all over the world played through numerous possibilities of missile potency. Variation spread with online forums, news blogs, and image boards acting as platforms for the communal call and response. When googling this missile incident, different versions of the image appear. The initial for missile version coexists with the 40 missile version. Authenticity is decided on by the viewer. The more often an image is viewed, the more likely it makes the top of search results. An image viewed often enough becomes part of collective memory.

When movies are released in cinemas, the first copies circulated online are renditions filmed off the screen labeled cam versions. Shown are two cam versions of the same movie, both successfully spread via peer to peer networks by unknown directors. The lifespan of these versions extends until a proper DVD or screening copies appear. Filming a film involves several variables: distance to the screen, angle, noise level of the audience, and quality of recording equipment all affect the peculiarity of the new film. These permutations, however, are not tolerated by Hollywood Studios. Apart from economic reasons, aversions to these variations might have their origin in the monotheistic religions’ declaration of idolatry as a major sin. Passages prohibiting depictions of God in the Quran, Torah and Bible negate the authenticity and validity of variations and could be read as the original dogma of a copyright manifesto.

Idols are defined by an iconoclastic destruction that is also simultaneously productive. The modes of destruction resemble modification strategies in remix culture. Creations are based on the transformation of existing material. Previously relevant cultural production is reinterpreted to match a more current ideology. Idols are punished by production of further idols. These images documenting statues in a Utrecht cathedral attacked with iconoclastic zeal during the Reformation in the 16th century, are tourist photographs, all found in the online photography archive, Flickr. Susan Sontag’s statement from 1977 that “just about everything has been photographed” makes more sense than ever. Celebrity fakes are unofficial modifications of porn, mixing two separate identities. Celebrity faces mounted on bodies of porn models, the body parts are modular, varying faces occasionally share a body and vice versa. Often utilizing first person perspective porn as host videos, a dual simulation takes place. The simulation of direct interaction with the porn model and the simulation of unrelated body and face matching. Multiple realities coexist. The host body, the guest face, the temporary state of preparation for the combination, the combination of host body and guest face. Another logical reality is almost always omitted: the combination of porn model face and celebrity body.

These iPod models have been collected from Google’s 3d warehouse, an online archive for homemade 3d models. Each iPod is produced and uploaded by a different author. The idea of an iPod works as a recipe or musical score that can potentially lead to infinite variations. All manifestations from physical to virtual act as performances of the idea: no particular variation has the monopoly on authenticity. So the jurisdictional claim loses control and consequently also loses relevance. The increase of duplicates does not diminish the concept of aura, but rather emphasizes it. The seemingly anonymous growth resembles a living organism which encourages an animistic perception. Duplicates update themselves at greater speed than official objects, subject to economic and physical laws. The bootlegs on restricted potential to develop makes it a more viable entity.

The moment in which Zinedine Zidane gave Marco Materazzi a headbutt during the final of the 2006 Soccer World Cup grew into a popular meme. Hundreds of authors proposed variations of the iconic incident. Similar to the many worlds theory by quantum physicist Hugh Everett, originally published in 1957, a multiplicity of realities coexist. According to Everett, we live in a multiverse composed of a quantum superposition of very many, possibly infinitely many, increasingly divergent non-communicating parallel universes, or quantum worlds. Every historical What if compatible with initial conditions and physical law is realized. All outcomes exist simultaneously, but do not interfere further with each other, each single prior world having split into mutually unobservable but equally real worlds. According to the artist and musician Momus, every lie creates a parallel world: the world in which it’s true.

Innsbruck (Austria), 1981

Oliver Laric studied at the Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien, where he met fellow artists Aleksandra Domanović, Christoph Priglinger and Georg Schnitzer. Together, they created VVORK in 2006. An influential contemporary art blog, VVORK became popular for posting photos and videos of artworks with minimum descriptions, when blogging was mostly based on text and media-rich social networks were just being developed. Active until 2012, the site regularly featured visual documentation of artworks and exhibitions that reflected the group’s vision of the contemporary art world, and also suggested the idea of establishing connections between artworks rather than considering the work of an artist the isolated output of a single creator. VVORK also generated debate around the similarities in most contemporary artworks exhibited in art galleries, as well as the increasingly common experience of seeing art online rather than on site. Another influential aspect of the site, as noted by Michael Connor, is that it contradicted the widespread idea of net art being restricted to art created solely for a web browser (Connor, 2015). It introduced a wider notion of online art, which was based on the appropriation and re-use of a variety of media, expanding beyond the screen and into the gallery space as installations and sculptures, as well as digital prints. This became a defining feature of post-internet art.

Between 2006 and 2009, Laric explored different forms of appropriation and remix, creating compositions of user-generated content and stock images, as in 787 Cliparts (2006), a fast-paced animation depicting human figures performing different actions arranged as a choreography; 50 50 (2007 and 2008), a compilation of YouTube clips in which fans of hip hop musician 50 cent perform three of his songs; and Touch My Body (Green Screen Version) (2008), an artwork comprising a modified music video by Mariah Carey in which everything other than the singer’s body is masked in a Chroma Key green screen, allowing others to create new versions of the video. In these artworks, Laric shows his interest in questioning authorship and the uniqueness of the artwork by using found material and creating different versions of the same idea (as in 50 50), which ultimately lead to considering the artwork as a process with variable outcomes.

The themes present in Laric’s work over these years coalesce in Versions (2009-2012), a series of videos in which the artist elaborates a statement or lecture on the overarching presence of doubles, copies, remixes and variations of the same content in all aspects of our visual culture, from the doctored image of a missile test issued by the government of Iran in 2008 to reused scenes in Walt Disney’s animation films, memes, and deep fakes. True to the nature of this work, Laric subsequently created new versions, in which he introduced the subject of iconoclasm and pointed out to how it actually generates new images: inspired by the desecration of religious sculptures in the 15th and 16th centuries, he created new versions of vandalized statues by sculpting a 3D model with which he cast a series of polyurethane pieces. The pieces were cast in layers, using different pigments and powdered materials on each layer, and presented as series in which their uniqueness and multiplicity are patent. Icon (Utrecht) and Icon (Worcester), both from 2009, are initial examples of this technique, that Laric has also applied to later artworks, such as Relief (Utrecht) (2010-2011), Sun Tzu Janus (2012) or Hunter and Dog (2015). His interest extended to other historical periods and regions of sculptural production, as well as the art academy’s traditional practice of copying Greek and Roman art, as exemplified in Kopienkritik (2011).

The ability to generate perfect digital copies of physical sculptures and objects using a 3D scanner inspired Laric in the development of a series of works in which he either facilitates their open and endless reproduction, or he creates pieces that question both the authenticity and materiality of the sculpture. Key to this period are the projects Lincoln 3D Scans (2013), a website offering freely downloadable 3D scans of objects from the Usher Gallery and The Collection in Lincoln, and Three D Scans (2015), a collection of scanned artworks from different museums in Europe, also freely available and without copyright restrictions. In this phase of Laric’s work, the variations in pigmentation of a series of polyurethane copies give way to single sculptures made of fragments cast in different materials or using different pigments and powdered materials on each layer. The resulting pieces are both unique and apparently a mashup of different variations of the same sculpture, as in Sleeping Boy (2016) or Reclining Pan (2019). In this recent work, he has also deviated from making copies of existing sculptures to create new pieces based on hybrid creatures, such as Hundemensch (2018).

Oliver Laric has exhibited his work extensively in museums and galleries worldwide. Recent solo shows include exhibitions at the Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri (2019); S.M.A.K, the Municipal Museum of Contemporary Art Ghent, Belgium (2021); Kunstverein Braunschweig, Germany (2018); Metro Pictures Gallery, New York (2018); and Tanya Leighton, Berlin (2018). Other important shows include Photoplastik (2016) at Secession, Vienna; Oliver Laric: Versions at the MIT List Visual Arts Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts (2013); and Triennial: Surround Audience at New York’s New Museum in 2015.

He currently lives and works in Berlin.

Archey, K. (Jul 5, 2011). Review: Oliver Laric’s Kopienkritik at Skulpturhalle Basel. Rhizome. [EN] https://rhizome.org/editorial/2011/jul/05/oliver-larics-kopienkritik-skulpturhalle-basel/

Connor, M. (Feb 9, 2015). After VVORK: How (and why) we archived a contemporary art blog. Rhizome. [EN] https://rhizome.org/editorial/2015/feb/09/archiving-vvork/

Davies-Crook, S. (March 5, 2012). Oliver Laric: destroying an image. ExBerliner. [EN] https://www.exberliner.com/art/destroying-an-image/

Hontoria. J. (May 20, 2016). Oliver Laric: contra el canon. El Cultural. [ES] https://www.elespanol.com/el-cultural/arte/arte_internacional/20160520/oliver-laric-canon/126237819_0.html

Quaranta, D. (2011). The Real Thing: Interview with Oliver Laric. Artpulse Magazine. [EN] http://artpulsemagazine.com/the-real-thing-interview-with-oliver-laric